by Michael N. McGregor

When Americans talk about immigration, they tend to have one of two groups in mind: either the crowds of Latin American refugees massing along our southern border today or the waves of Europeans who swept into the country in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

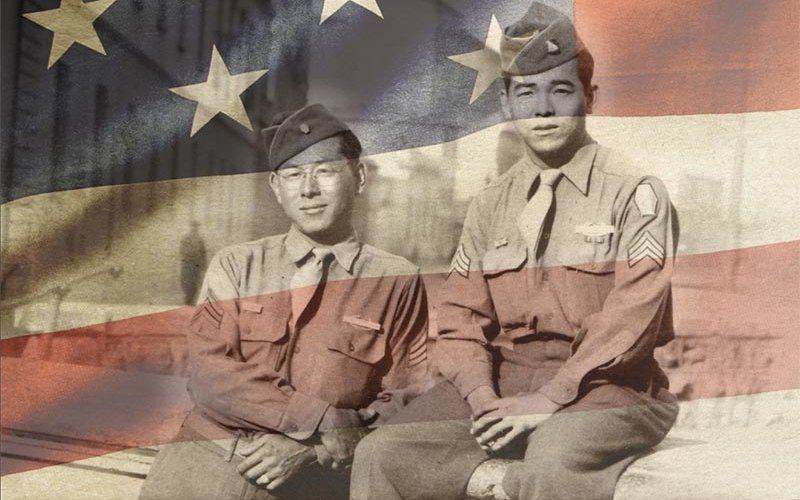

Almost entirely forgotten are the Asian immigrants who settled mostly along the West Coast at roughly the same time Europeans were flooding in. Among them, the Chinese suffered the worst early experiences, subjected as they were to humiliations and killings and legislated exclusion from the country. But it was the Japanese, both foreign- and domestic-born, who, in 1942, at the direction of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, became the only Americans (other than enslaved Blacks) ever rounded up and incarcerated solely because of their ethnicity.

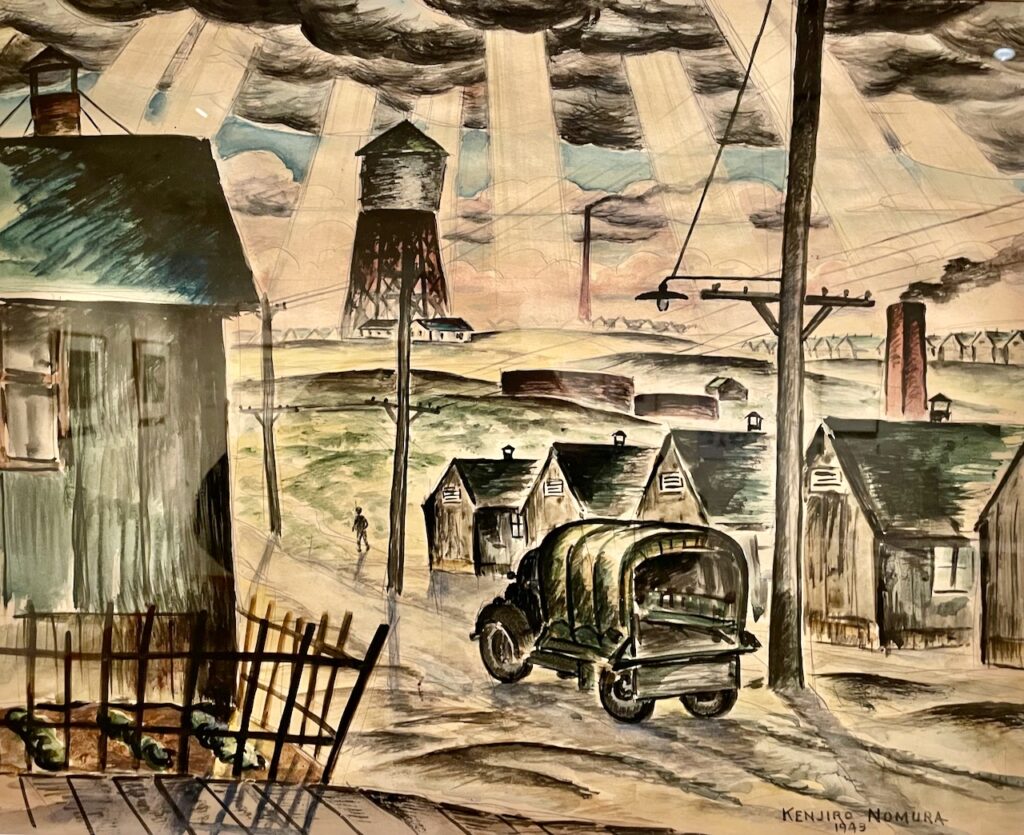

The basic story of Executive Order 9066–by which people of Japanese ancestry (whether American citizens or not) were deprived of their civil rights and forced to leave their homes, businesses, and farms to live in internment camps in desolate areas–is well-known today. Children often learn about it in school. What isn’t generally known or taught, however, is the devastating effect the internment experience and its aftermath had on the minds and lives of those forced to endure it.

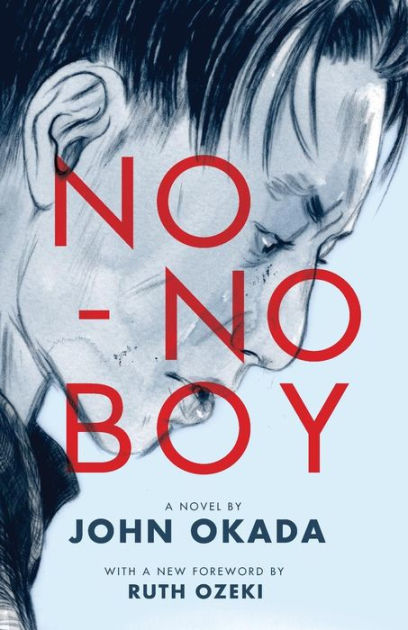

I’ve written about that dark period myself, both here and elsewhere, but my observations were those of an historian, my understanding that of an outsider–until this past month when I finally read a book I’d intended to read for years: John Okada’s No-No Boy.

Before I discuss the book’s content, let me state clearly that No-No Boy is not just a great book about the experiences of Japanese Americans; it’s a great book, period. Not only is it beautifully written, it’s also unflinchingly honest and fair and heartbreaking.

Published in 1957, No-No Boy tells the story of Ichiro, a young Japanese American man returning to his hometown of Seattle in 1946. Instead of returning from the war like others in the city’s Japanese community, he is returning from two years in prison, where he was sent for answering ‘no’ to two questions every young man of Japanese descent was asked: Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States? Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the country? (His answers are the no-no of the book’s title.)

The first thing that happens to Ichiro when he reaches Seattle is a former acquaintance who did serve in the military spits on him. Worse is yet to come as he faces accusations of treason and betrayal as well as the doubts, regrets, and shame in his own mind.

While Ichiro is always central, part of what makes the book so good and devastating (as well as pertinent to discussions about immigrants today) is how well and fairly Okada renders not only Ichiro’s psychological state but those of everyone he encounters–from immigrants like his mother who remain devoted to Japan to the whites who have little idea what someone like Ichiro is going through.

Some in the book are kind and some are cruel, but no one is reduced to a type or a category. All have their reasons for all acting and speaking the way they do. And Okada gives them all their due, even those who seem most awful.

Okada wasn’t afraid to interrogate his own culture as well as the larger white culture around it, or to drill down into the various sicknesses and cruelties at the family and interpersonal levels.

Rendered in a voice that’s both distinctive and perfectly in tune with its time and characters, Okada’s willingness to look unflinchingly at how people truly think and treat each other makes No-No Boy one of those rare books—like Stoner or Revolutionary Road—that seem to hold the raw and bloody heart of life in their hands.

Here, for example, is Ichiro thinking about his younger brother, Taro, who detests him for not serving in the military and plans to enter the post-war army himself:

Taro, my brother who is not my brother, you are no better than I. You are only more fortunate that the war years found you too young to carry a gun. You are fortunate like the thousands of others who, for various reasons of age and poor health and money and influence, did not happen to be called to serve in the army, for their answers might have been the same as mine. And you are fortunate because the weakness which was mine made the same weakness in you the strength to turn your back on Ma and Pa and make it so frighteningly urgent for you to get into uniform to prove you are not a part of me. I was born not soon enough or not late enough and for that I have been punished. It is not just, but it is true. I am not one of those who wait for the ship from Japan with baggage ready, yet the hundreds who do are freer and happier and fuller than I. I am not to blame but you blame me and for that I hate you and I will hate you more when you go into the army and come out and walk the streets of America as if you owned them always and forever.

Laid out in this book, in sometimes agonizing, sometimes breathtaking clarity, is the immigrant experience: the awful decisions and compromises and consequences America demands of those who seek only to be accepted, fully and respectfully, as fellow citizens.

A few links:

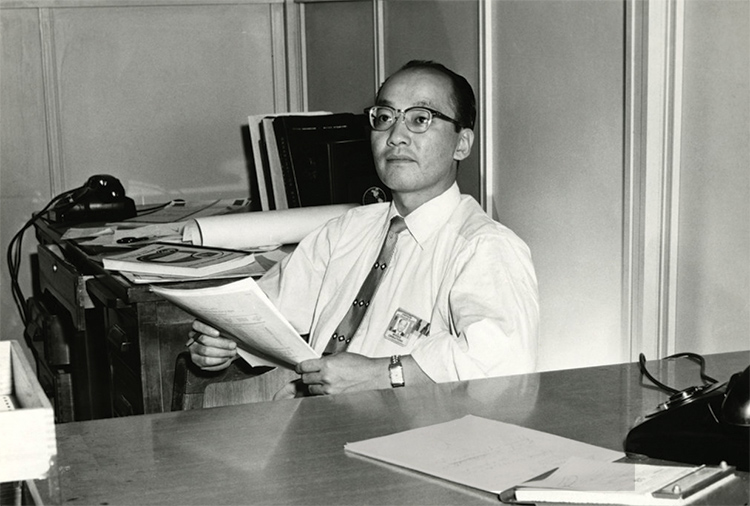

- John Okada’s personal story is as agonizing as that of the main character in his only novel. You can read about his difficult life and what became of his second book in “The Legacy of No-No Boy” by Vince Schleitwiler, published in the December 2019 issue of University of Washington Magazine.

- “‘No-No Boy’ went from unknown book to classic thanks to UW Press and Asian American writers. Now, it’s at the center of a controversy,” The Seattle Times, June 13, 2019

- Densho, a website whose mission is to “preserve and share history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans to promote equity and justice today.”

Note: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org, where your purchases support local bookstores. If you purchase a book through a click on this website, I will earn a small commission that helps defray the costs of maintaining WritingtheNorthwest.com.

Leave a Reply