Sometimes you find the most interesting and informative visions of an area like the Pacific Northwest in out-of the-way places. After reading an article in the Seattle Times, my wife and I traveled out to Edmonds, WA, the other day to view the works of Kenjiro Nomura, an amazing and quintessentially NW artist who moved to Washington state from Gifu, Japan, in 1907 when he was 11.

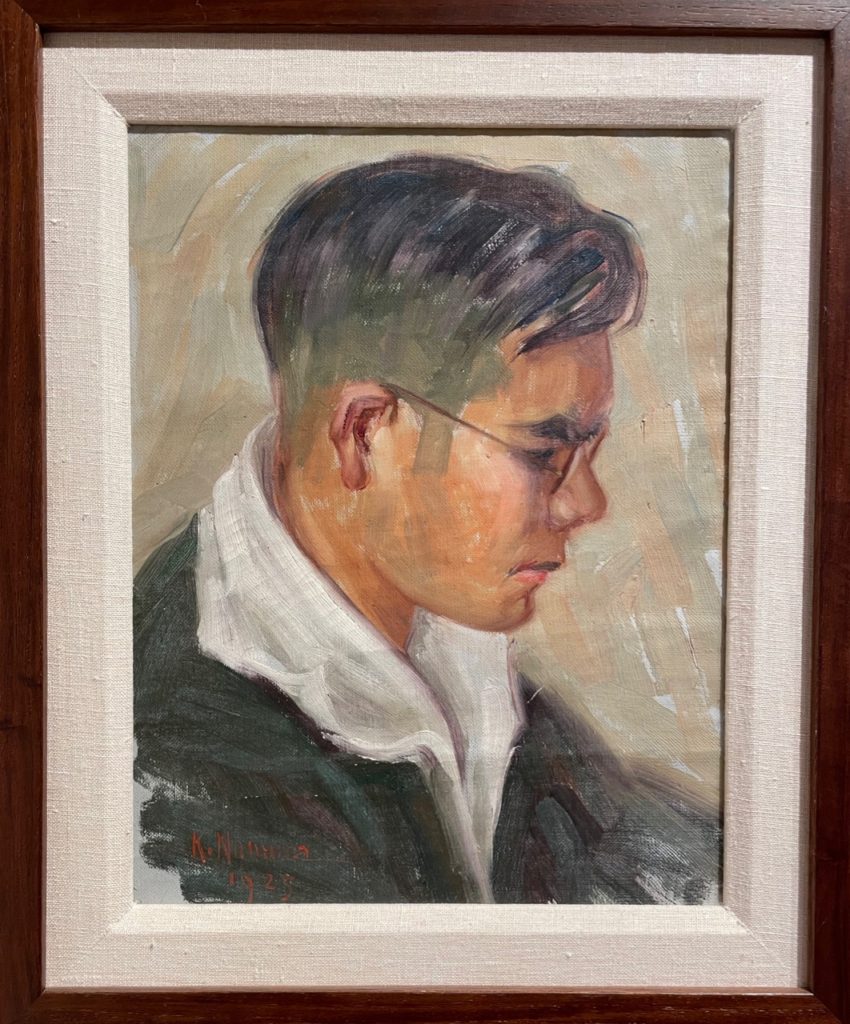

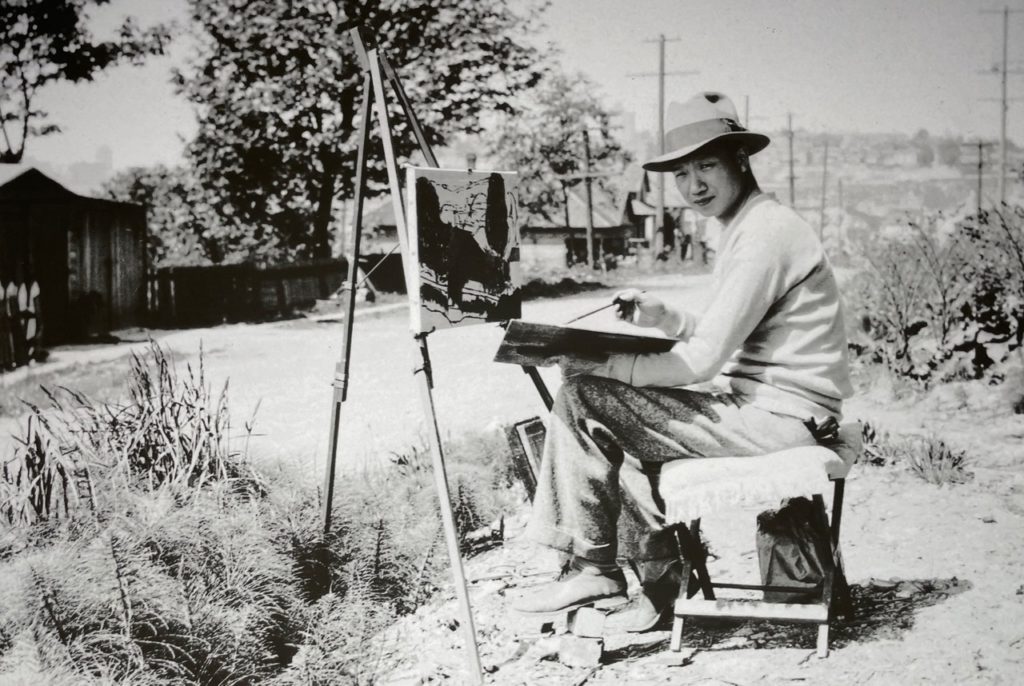

Within a few years, Nomura was studying with the Dutch immigrant artist Fokko Tadama, who, according to the exhibit, “taught a plein air style of painting with loose brushwork that was similar to impressionism.” Like Nomura, many of Tadama’s students were of Japanese heritage and began to be recognized for the quality of their work while still students. That is to say, a group of talented young Japanese and Japanese American artists was thriving in the Seattle area as early as the 1910s.

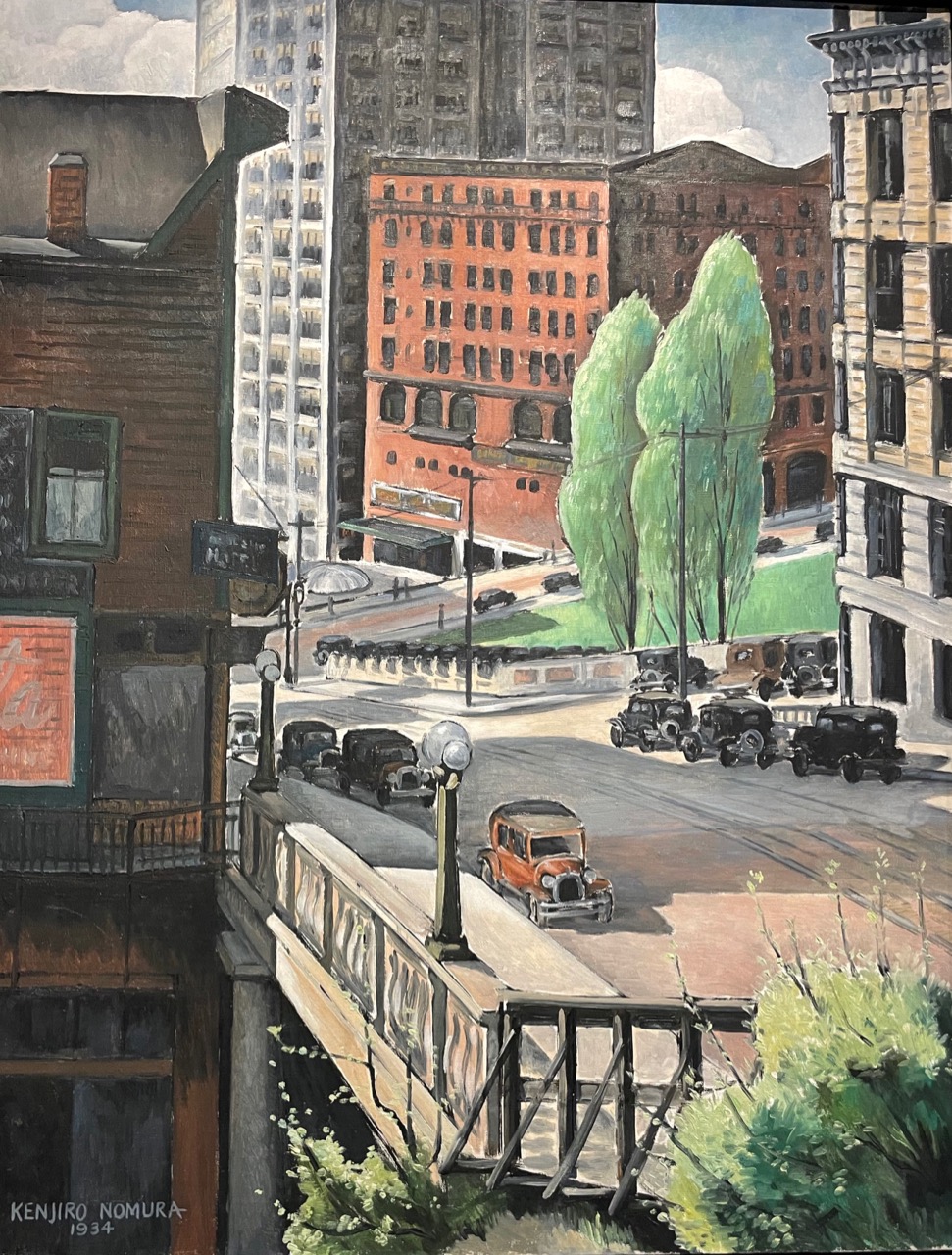

Throughout the 20’s and 30’s, Nomura continued to grow as an artist, painting both urban scenes and landscapes in oils and watercolors. Somewhere around 1930, he moved beyond Tadama’s impressionist style and developed a more modernist style of his own: “a personalized approach that emphasized form, color, texture, and the atmospheric light unique to this region.” When the Seattle Art Museum opened in 1933, Nomura was the first local artist to have a solo exhibition there. Soon, his work was being exhibited across the country.

During the depths of the Depression in 1933-34, Nomura was part of the New Deal’s Public Works of Art Project, a program meant to help struggling artists. A year later, he became part of Seattle’s progressive Group of Twelve, a collection of leading local artists from many backgrounds. In other words, he was a full and integral part of a local American art scene with a growing national reputation…

…and then came Pearl Harbor and FDR’s Executive Order 9066, ordering the incarceration of almost 120,000 Japanese Americans, 2/3 of them American citizens.

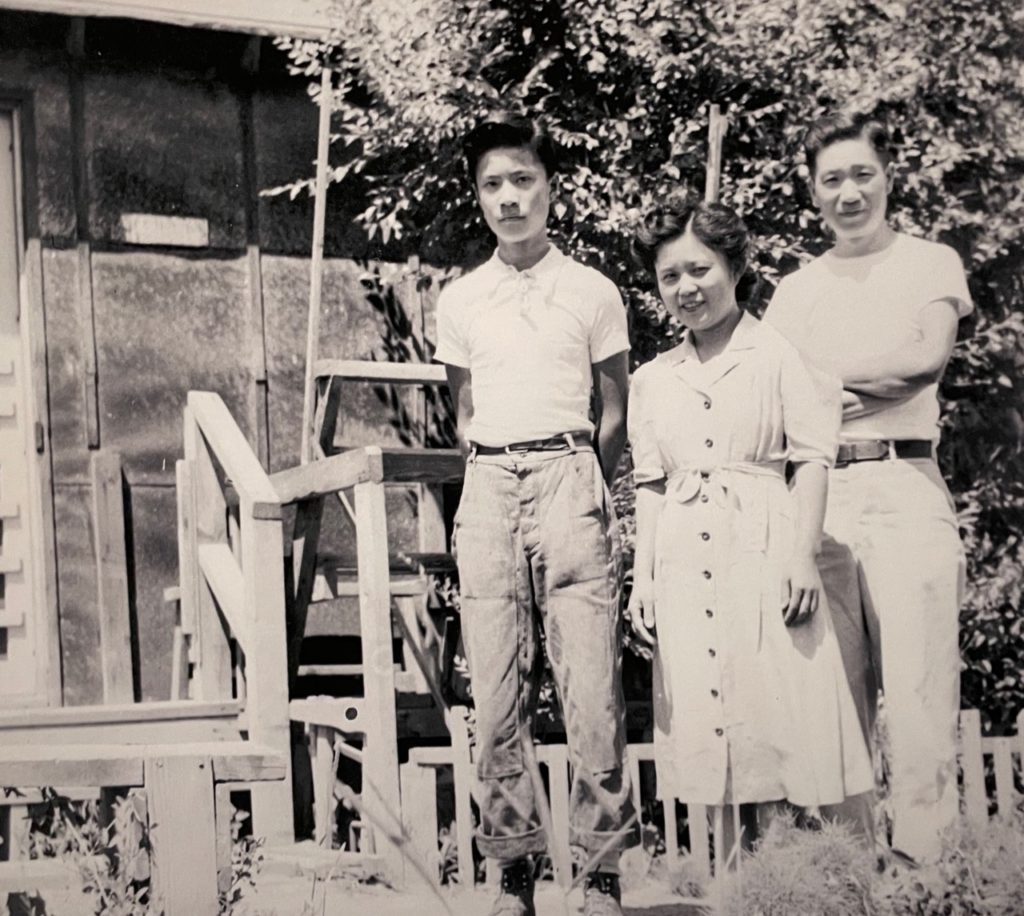

Nomura was interned, with his wife and son, at a collection camp called Harmony, where the Puyallup Fairgrounds stand today. From there, they were sent to the Minidoka Relocation Center in a wasteland in south-central Idaho, where they remained until the end of WWII. (“The first thing that impressed me was the bareness of the land,” said camp resident Shozo Kaneko in a 1943 interview. “There wasn’t a tree in sight, not even a blade of green grass. Coming from the northwest where there was a lot of green fields and forest, the sights staggered most of us who had never seen anything like that before.”)

Here’s what one of the exhibit signs says about the effect on Nomura of his time at Minidoka: “The same government who paid for his artistic services less than ten years earlier had now created a devastating personal situation that would affect the rest of his life. He and his wife and son returned to Seattle in 1945 only to have his wife commit suicide the following year.”

When Nomura reluctantly resumed painting after his wife’s death, he turned to abstraction and soon his work was popular again. The height of his success came in 1955 when his paintings were part of a major exhibition of NW artists in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and a show called Eight Washington Painters at the Portland Art Museum. A year later, his work was included in an exhibition titled Pacific Coast Art that traveled to top museums around the country. But that June, at only 59 years of age, Nomura died from complications from surgery.

What I find most intriguing, saddening, and infuriating about Nomura’s story is the promise his talent, associations and success represent–a promise cut short for so many Americans and hardworking immigrants in the NW by prejudice and fear of “the other.” In the days before he was sent to Minidoka, Nomura said about his art:

“My desire in painting is to avoid the conventional art rules, so that I can be free to paint and approach Nature creatively. I have gradually and almost unconsciously been influenced by the work of early Japanese painters. Now realizing this influence, I am consciously trying to utilize those qualities that I want, such as color, line and simplicity of conception, in my own style of painting. Due to the great difference between the Western style of painting and the Japanese, the problem is a very difficult one, but I am devoting every effort to achieve this.”

What other fine integrations of East and West–what advantageous hybrids and creative leaps–did we lose when a vital population was uprooted; deprived of their homes, businesses and artistic pursuits; and sent to live in concentration camps because of a deep-seated racism in this country?

I’m grateful to Cascadia Art Museum curator David F. Martin, who put the Nomura exhibit together, not only for introducing me to some of the most moving and impressive art I’ve seen in a long time but also for telling Nomura’s story: for writing the Northwest in this too-rare and much-needed way.

Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist: An Issei Artist’s Journey runs through February 20, 2022, at the Cascadia Art Museum at 190 Sunset Ave. S., #E in Edmonds, WA.

Exhibit hours are:

11 a.m.-5 p.m. Thurs.-Sun.

Ticket prices are:

Adults: $10

Seniors: $7

Youth (0-18): Free

Students: Free

To learn more about the exhibit, go to the Cascade Art Museum’s website.

For an in-depth look at Nomura’s life and art, consider purchasing art historian Barbara Johns’ Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist, available for $39.95 on the CAM site.

Leave a Reply