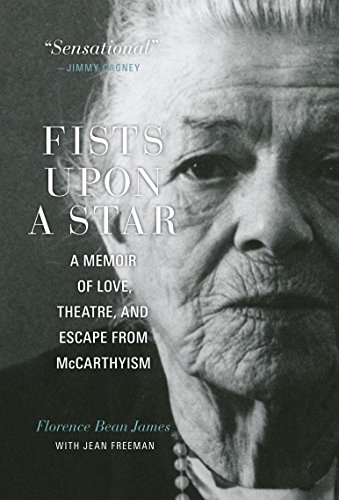

Recently, I came across a fascinating but little-known book that should be read by anyone interested in race relations, theater, or Red Scare accusations in the Pacific Northwest. Titled Fists Upon a Star: A Memoir of Love, Theatre, and Escape from McCarthyism, it tells the story of Florence B. James and her husband Burton James, who were pioneers and innovators in Seattle theater, including assembling the first all-Black company in the NW.

Although Florence James completed the book (with help from Canadian actress Jean Freeman) before her death in 1988, it wasn’t published until 25 years later. And when it was, it received little notice in the Northwest or in the U. S. in general, probably because its author was long dead and its publisher was the University of Regina Press in Canada, the country James fled to after being persecuted for the theater she dared to put on an American stage.

Florence and Burton started out in New York City but moved to Seattle in 1923 to take teaching jobs at Cornish College, the celebrated arts school that was still in its first decade then. Not content to be teachers only, they wanted to stage the kinds of cutting-edge and socially relevant plays they were most interested in. But when they tried to mount a production of Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, the Cornish board of directors refused to sanction “a supposedly ‘immoral’ play.”

Local theater leaders came to their defense but the board wouldn’t budge, so the Jameses resigned and started a company of their own, the Seattle Repertory Playhouse. When one of their defenders, Glenn Hughes, took over the University of Washington drama department, he hired them to teach there, and soon they were drawing increasingly larger audiences to an aging brick building near campus they’d converted into a theater.

Every part of the Jameses’ story is fascinating, including the accusations brought against them in 1948 of being communists, when they were forced to appear before Washington State’s newly formed Joint Legislative Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities (a forerunner of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s circus at the federal level). But the part I find most fascinating is their establishment of Seattle’s Negro Repertory Company in 1935.

As Florence tells the story, the Seattle Repertory Playhouse was flying high when, in 1932, in its fifth season, patrons who had purchased season tickets in earlier years sent notes saying they couldn’t afford them anymore. With the Depression hitting the Northwest hard, it looked as if their once-thriving venture would have to fold.

“We were out of oil and the electricity had been cut off for nonpayment of bills,” Florence writes. They burned odd bits of wood for heat, made a deal with power company, and “went on rehearsing, paying something here and something there” when they could. Through “a series of timely miracles,” as one of their players wrote in the company log, they were able to hold out until, in early 1935, they learned that one of the Roosevelt administration’s newly created agencies, the Works Progress Administration, had a program called the Federal Theatre Project, intended to employ out-of-work artists.

“When we discovered that this was not to be a ‘pork barrel’ for Broadway and Hollywood,” Florence writes, “we prepared a brief for what we decided to call a Negro Repertory Company.” When their project was accepted, their first production was of a play called Noah, translated from French.

“We used Black music and introduced Black dancing to express the jubilation of Noah and his family when the flood recedes,” Florence writes. “Reviewers expressed amazement at the talent of people ‘taken from the scrap-heap of unemployment.’” She goes on to quote a reviewer from the Seattle Star who wrote: “This all-Negro cast put on a performance so rich, so full of promise, it was tragic in its implications. Tragic because these people who have so much to contribute have so long been wasted.”

For too brief a time, Black theater flourished on a Seattle stage in the depths of hard times, with all-Black shows playing to full houses night after night. The cast members were all amateurs, drawn mostly from Seattle’s First African Methodist Church, their talent, as the Star reviewer wrote, too long wasted.

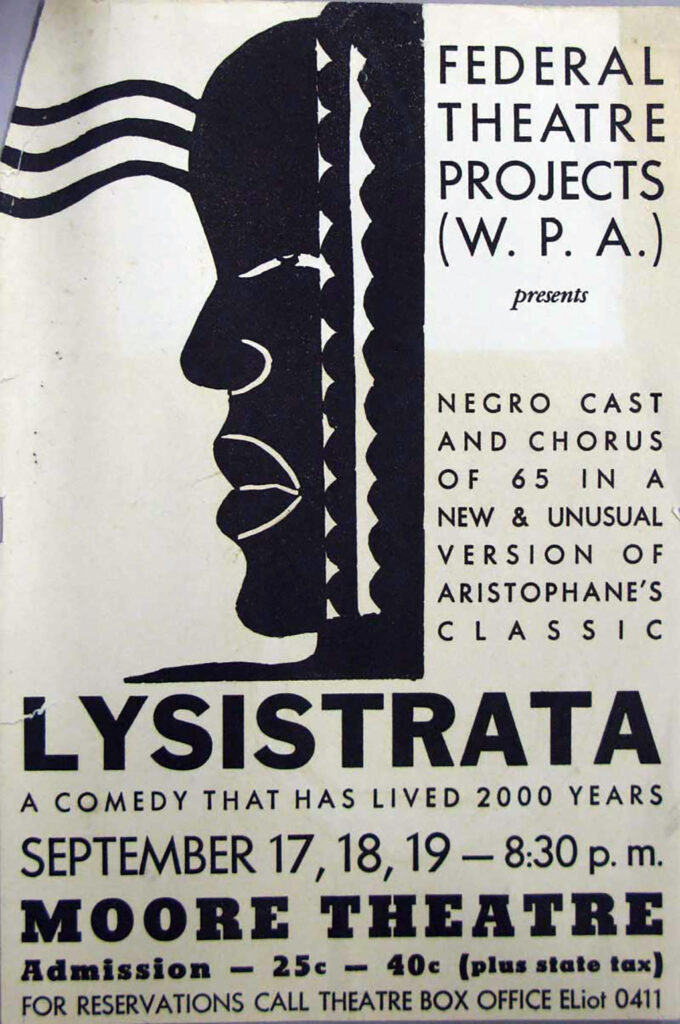

When the group discovered that there were few good plays for Black actors, they began writing their own, but it was their production of a 2,000-year-old play, Lysistrata, that brought them the most attention. Called “indecent and bawdy,” their version of Aristophanes’ comedy was closed down “in the interest of the Federal Theatre Project.” The Negro Repertory Company continued to exist until Federal Theatre Project funding ended in 1939, but by then the Jameses had moved on.

Once the members of the Negro Repertory Company had gained production skills, Florence tells us, they began to help with White productions. “They came over willingly, joyfully, and everybody worked together. Whites taking orders from Black stage managers and technicians. Blacks working amicably with Whites–no Black power, no White power, no tensions, no frictions anywhere, just people joined in the effort of doing a job and doing it well.

“The experience of discovering talents among people who had been doing dull, mundane jobs was a constant source of joy to us. To see the colossal waste of such human resources, the most valuable assets to any country, and to realize what could have been accomplished and what this accomplishment could have meant was staggering.”

Decades passed before Seattle audiences saw a revival of Black theater. But just this year, the city’s ACT (A Contemporary Theatre) premiered a play by Seattle playwright Reginald André Jackson that explores the neglected history of Black theater. Titled History of Theatre: About, By, For, and Near, the show’s protagonist, a playwright seeking to write a new play about the history of Black theater, goes back in time and asks the members of the Negro Repertory Company for help.

~ ~ ~

(Click here to read Sarah Guthu’s excellent summary of the Negro Repertory Company’s history on the University of Washington’s “The Great Depression in Washington State” website. It includes illustrated histories of the group’s Lysistrata and two other productions. And click here to read Guthu’s equally fine writing about the Jameses and their Seattle Repertory Playhouse, from which some of the facts in this post are drawn.)

Other links:

Negro Repertory Theatre by Paula Becker, an in-depth History Link look at the NRC, its productions, and its national associations

Fists Upon a Star: A Memoir of Love, Theatre, and Escape from McCarthyism by Florence B. James–read an excerpt and/or order directly from the University of Regina Press ($27.95 CDN, paperback, 360 pages)

Leave a Reply