by Dr. Laura Laffrado

[Dr. Laura Laffrado is a Professor of English at Western Washington University. Her full bio can be found at the end of her essay.]

In the last decades of the 19th century, the Pacific Northwest, especially the far corner of northwestern Washington, was a remote place where it was hard to earn a living and difficult to find the leisure to write, even if you were literate. If someone did manage to write something, the region was so distant from Northeastern publishing centers, there was little chance the writing would be published and even less that it would achieve literary success.

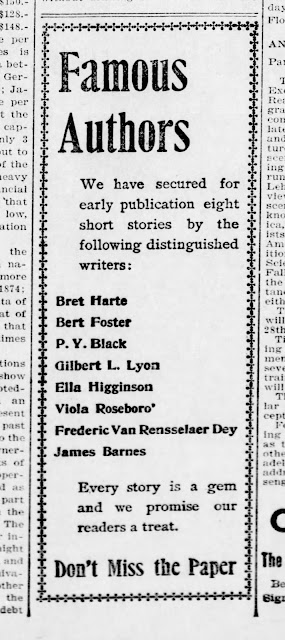

Yet there was one writer there—a woman—who was not only being published but winning national awards for her work. The Chicago Tribune claimed she had “the hallmark of genius.” The San Francisco Chronicle said her characters were “as strong, as individual, as any created by Dickens or Thackeray.” Others compared her writings to those of Jane Austen, Sarah Orne Jewett, Jack London, and Leo Tolstoy.

She was, in fact, the first Northwest writer to be nationally—and even internationally—recognized, a woman who, according to the Kansas City Star “revealed the wildness and witchery of that northwestern corner where, watched by immemorial pines, Puget Sound lies sparkling in the clean air, and the horizon sweeps down to the great blue ocean.” For readers across the country, she put the Northwest on the literary map.

Yet today Ella Rhoads Higginson is almost completely unknown.

When I first stumbled upon Higginson’s substantial holdings in the Washington State archives a few years ago, I was stunned, confused, excited, and nearly overwhelmed by unanswered questions. Who was this woman I’d never heard of? What kinds of things had she written? What could the twelve linear feet of her archive possibly contain? Why hadn’t I heard of her?

As I dove into researching her life and work, I learned that many people across the nation and around the world were first introduced to the Pacific Northwest when they read Higginson’s award-winning writing. Her descriptions of the majestic mountains, vast forests, and scenic waters made the distant and unfamiliar Northwest captivating. “Here comes a woman,” Philadelphia’s Globe Quarterly Review said, “all the way from Seattle, breathing the air of the Western mountains and seas.”

Remarkably, in her almost 80 years of life, Higginson (1862?-1940) authored over eight hundred works of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and screenplays. She was published by the prestigious Macmillan Company in New York, earned best-story prizes from popular magazines such as Collier’s and McClure’s, and was Washington State’s first Poet Laureate. Popular composers set her poems to music and celebrated singers, including the great Enrico Caruso, performed and recorded them.

By the time Higginson died, however, both she and her work had been forgotten.

Higginson’s writings were especially notable in her day because they were set in Oregon and Washington, with infrequent forays into Alaska, British Columbia, and Idaho. At the time, the Northwest was not only remote and thinly populated but also largely male, and Eastern readers were captivated by it, especially as described by a woman.

Higginson’s first publication came in 1876, when an Oregon newspaper printed one of her poems. She was 14 years old. By then, her family had moved west from Kansas, where she was born. Although she attended public school, she was privately tutored and benefited from her parents’ substantial library. She might have become known exclusively as an Oregon writer if she hadn’t married Russell Carden Higginson (a distant cousin of New England author and editor Thomas Wentworth Higginson) in 1885 and moved with him to what is now Bellingham, Washington, where she lived the rest of her life.

It was a poem, too, that first earned Higginson a national reputation. When “Four-Leaf Clover” was published in 1890, it quickly became a nationwide—and then international—sensation. Appearing in periodicals and on postcards (see below), greeting cards, calendars, paper weights, and other ephemera, it was also set repeatedly to music. Even today, it is the one piece of writing her name is still connected to.

A savvy promoter of her own work, Higginson played on the popularity of her breakthrough poem every way she could. She named her dog Clover and her house Clover Hill. She wore four-leaf-clover jewelry and led an unsuccessful campaign for the wild clover to be named the official Washington State flower. She had four-leaf clovers imprinted on many of her books’ covers and used them on her bookplates. She even wrote a literary column for the Seattle Times called “Clover Leaves.”

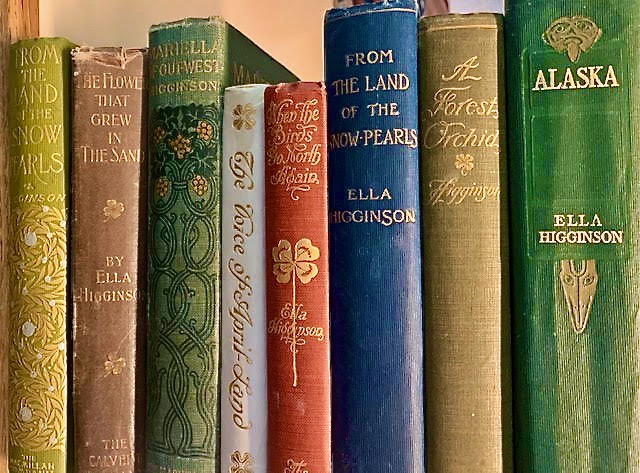

But although “Four-Leaf Clover” was incredibly popular, it was only a tiny part of her body of work. Among her most important books are the short-story collections From the Land of the Snow Pearls (1897; originally published in 1896 as The Flower That Grew in the Sand) and A Forest Orchid (1897), the poetry collections When the Birds Go North Again (1898) and The Voice of April-Land (1903), and her one completed novel, Mariella, of Out-West (1902), which some reviewers called the best novel of the season.

Her last book, the literary travelogue Alaska, the Great Country (1908), was called essential reading for any intrepid traveler headed north to Alaska.

All of these books sold well, ran through multiple printings, and were positively reviewed nationally and internationally. However, like many once-popular women writers, Higginson’s literary star dimmed in the early 20th century. Her books went out of print and her fame faded. Near the end of her life, aggrieved at being forgotten, she wrote on a folder of saved correspondence, “Letters from famous folks; and from publishers, proving that I didn’t need to seek publishers—they sought me.” (Emphasis in original).

Higginson died at 78 on December 27, 1940, and is buried in Bayview Cemetery in Bellingham, beneath a self-designed granite marker featuring four-leaf clovers, quotations from her poetry, and the proud line, “Ella Higginson, Poet-Writer.” It seemed at the time that no one would know her name or her work again.

Fortunately, though, after decades of obscurity, Higginson and her work have been rediscovered, not only by me but by other scholars and readers. Her writings are even being taught in high school and college courses today. Much remains to be done, however, to return her to the prominent position she deserves, as the first of the Pacific Northwest’s literary stars.

A few links:

Dr. Laffrado’s book: Selected Writings of Ella Higginson: Inventing Pacific Northwest Literature

The Ella Higginson Blog–maintained by Dr. Laura Laffrado (lots of great stuff here, including lists of Higginson’s works and news of current writing about her.)

Dr. Laura Laffrado page at Western Washington University.

Ella Higginson site maintained by WWU.

Ella Rhoads Higginson bio at Oxford Bibliographies.

Ella Higginson entry in the Oregon Encyclopedia.

Ella Higginson books for sale! (Disclosure: WNW is an affiliate of Bookshop.org, where your purchases support local bookstores. If you purchase a book through a click on this website, we will earn a small commission that helps defray the costs of maintaining WritingtheNorthwest.com.)

~~~~~

Dr. Laura Laffrado is an award-winning Professor of English at Western Washington University. Among her books are Uncommon Women: Gender and Representation in Nineteenth-Century US Women’s Writing and her most recent book, Selected Writings of Ella Higginson: Inventing Pacific Northwest Literature, which received the Society for the Study of American Women Writers 2018 Edition Award. She is currently at work on a biography of Pacific Northwest writer Ella Rhoads Higginson.

Leave a Reply