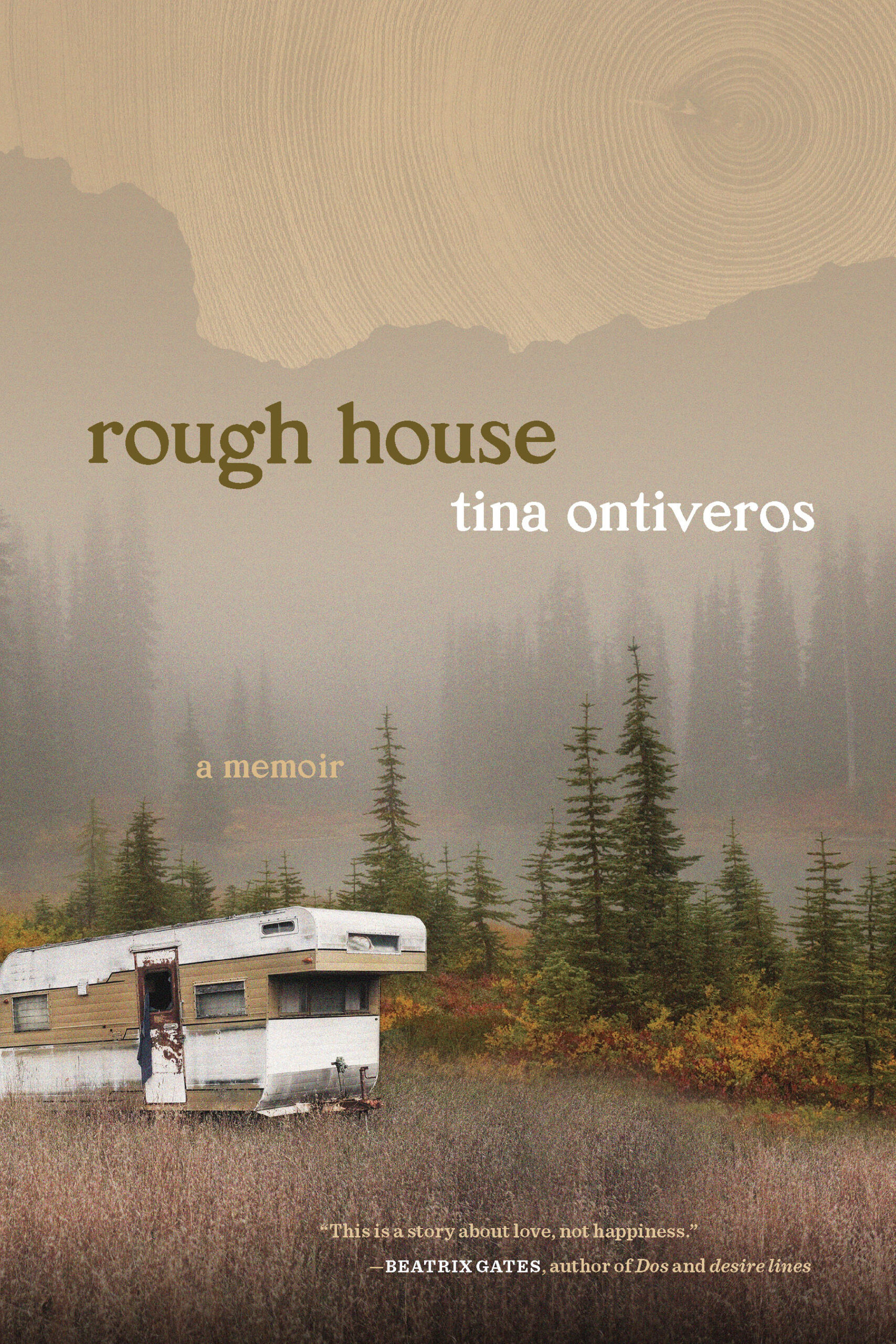

At the heart of rough house—Tina Ontiveros’s difficult yet moving memoir about growing up poor in the damp forests of the Pacific Northwest and, when her family breaks apart, the brown dryness of The Dalles, Oregon—stand two people and a question.

One of the two is Ontiveros’s childhood self, revealed not only through her adult memories but also the stories her parents tell about her earliest years, some true, some exaggerated or made up altogether. The true stories come from her mother, the made-up ones from her father, Loyd, the second and more ambiguous of the book’s two main characters.

Loyd is an itinerant logger from a family of loggers at a time when Northwest logging is in decline. He drags his family from place to place, lodging them in various trailers and other inadequate shelters. Although he works hard, he falls off the wagon repeatedly, insists on controlling those around him, and strikes with his fists when he feels someone has crossed him, including the mother of his children. Loyd is the kind of person who squanders his life and drives away others, never able to stay on track for very long.

As Ontiveros writes at the end of her first chapter—a chapter in which we witness her father’s brutal way of teaching her to ride a bike—Loyd “left nothing much physical behind him on this earth. No poetry or paintings, no endowments or discoveries to share with humankind…Mostly his existence was primal flashes of intensity in different places, always a sense of adventure and danger. There was a sort of balance to his living, creativity and destruction in equal measure. Always harm. Always love.”

In many ways, Loyd is simply the product of the world he lives in, a world in which timber barons and corporations use and misuse a fungible and ultimately disposable cadre of rootless men to extract the riches of Northwest forests for personal gain. Like many men who make their living with their bodies, he tends to respond to the world in physical ways, particularly those that cause Ontiveros’s mother to leave him: “drinking, drugging, cheating, and hitting.”

But behind those physical responses lie deeper emotions often perverted by the way these men have grown up and lived and, as the last two words of the quote above suggest, those emotions can be expressed in positive ways, too. Which leads us to both the question at the book’s core—Why does Loyd’s daughter not only return to him again and again but choose to write a book about him?—as well as a possible answer.

“I lived in a small body then,” Ontiveros writes at the end of chapter three, “and when Loyd knelt down and talked to me, to show me the miracle of an unbroken sand dollar or a newly forming inlet, he looked like a man at prayer. What I mean to say is that he made me feel like I deserved to take up space. From his moments of careful attention, I learned to expect some small amount of worship from the world. From his violence, desperate apologies, and absences, I would discover that the same sparkling fires that fueled his creativity could burn out of control, leaving a landscape stripped of life. Loyd would hurt and fail me in a hundred ways, but first he taught me to wonder, gave me love without condition, and moments where I felt holy.”

Ontiveros’s mother’s love for Loyd reaches a breaking point when he holds a gun to their adolescent son’s head. And Ontiveros reaches a similar point when he violates her trust in an especially vile manner. The violation and its aftermath are, in many ways, the book’s high point. After smoldering for half of the book’s 188-page length, Ontiveros’s writing suddenly catches fire as she finally faces the kind of man her father is. Out of that fire comes a deeper question: Can you continue to love a man who does a thing like that?

But something else is born in that fire too: The stronger woman Ontiveros will become, a woman who is not only able to see her father—and her mother—with clear eyes, but also to stand on her own, with her own strength; forge a life for herself out of tools her parents have inadvertently given her; and find a way to not only love but embrace the people she came from.

In the end, of course, the story doesn’t belong to Loyd, it belongs to his daughter, who has the choice to tell it in her own way. Although it is often a brutal story, it is told with love. And it is that love that allows Ontiveros to not only rise above the violence, misogyny, and suspicion often endemic to the world she came from, but also bring some acceptance to that world, helping us to understand it.

Contrary to popular belief, you can sometimes tell a lot about a book by its title. In addition to the double meaning of physical fun and difficult circumstances, it’s significant that rough house is printed in lower case. Ontiveros is shining a light on minor characters whose stories, though filled with poverty and violence, are worth telling—and worth reading—for what they reveal about the hardships many Americans face, as well as how those Americans—especially women, like Ontiveros—find a way forward despite the odds.

rough house

by Tina Ontiveros

Oregon State University Press

2020

$18.95

Two other compelling books about Northwest women finding their way forward out of poverty, violence, and isolation (both set in Idaho):

Educated by Tara Westover (Random House, 2018)–National Book Critics Circle Award finalist–“Beautiful and propulsive . . . Despite the singularity of [Westover’s] childhood, the questions her book poses are universal: How much of ourselves should we give to those we love? And how much must we betray them to grow up?”—Vogue

In the Wilderness by Kim Barnes (Doubleday, 1996)–Pulitzer Prize finalist–“In the Wilderness is the story of this poet’s journey toward adulthood, set against an interior landscape every bit as awesome, as wondrous, and as fraught with hidden peril as the great Idaho forest itself.”–Amazon.com

Leave a Reply