Earlier this week, the winners of the 2022 Oregon Book Awards were announced. While the awards honor books by Oregon writers rather than books specifically about Oregon, a fair number of the award finalists are usually set in the state or explore some aspect of it.

Soon, I’ll be posting a review of one of this year’s finalist, rough house by Tina Ontiveros (this site’s first book review), but today I’m thinking of a wonderful and unique award winner I picked up at the ceremony a few years ago.

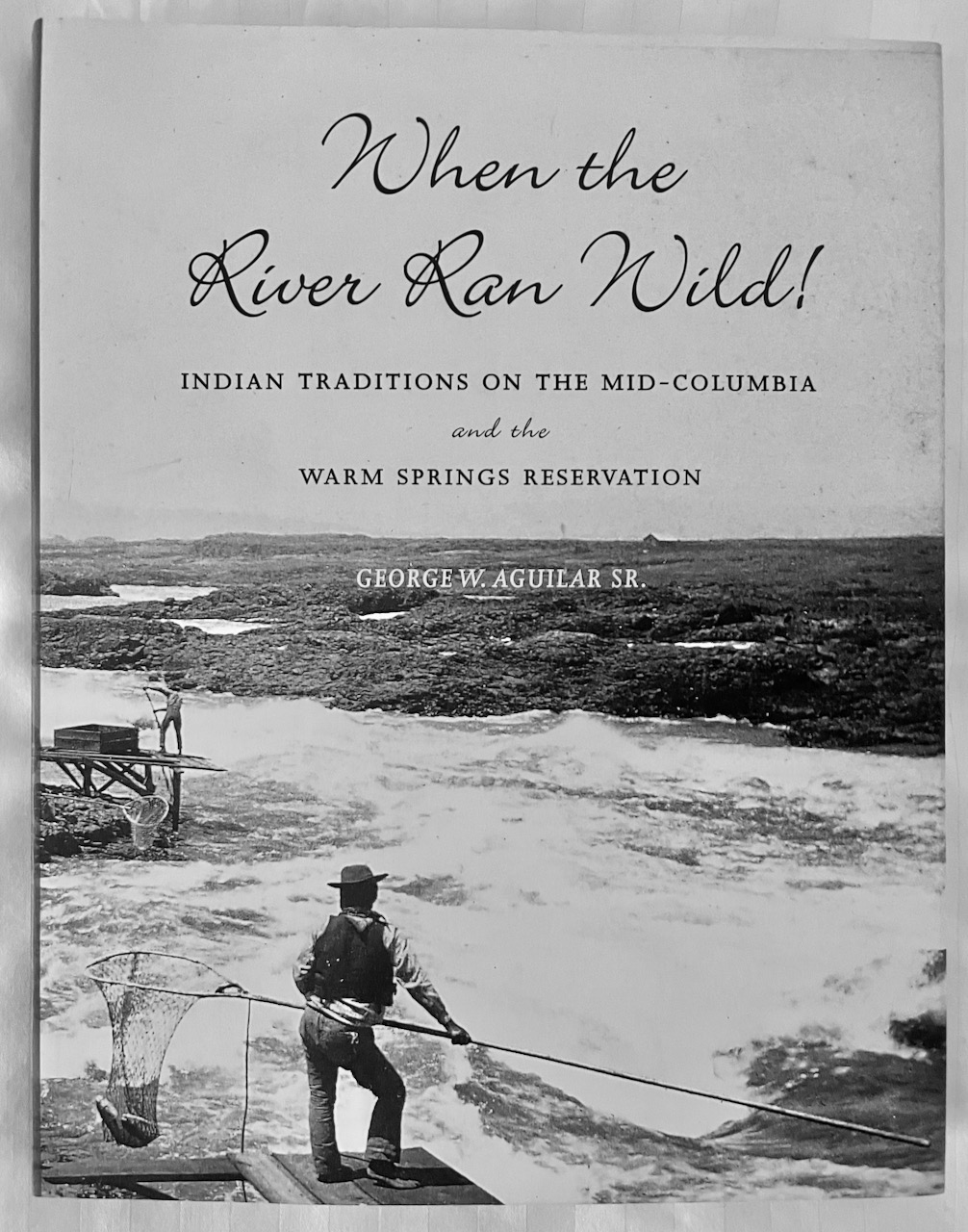

The book, written by George W. Aguilar, Sr., a descendant of Chinook Indians who lived, fished, and traded along the Columbia River for centuries, is called When the River Ran Wild!: Indian Traditions on the Mid-Columbia and the Warm Springs Reservation. The subtitle makes it sound like an academic text, but Aquilar’s book is so much more than that.

While he quotes from some academic sources–such as Robert H. Ruby and John A. Brown’s classic look at the Columbia Chinook, The Chinook Indians: Traders of Lower Columbia (University of Oklahoma Press, 1976)–Aquilar’s main sources of information are other descendants of the Columbia tribes. And his intention isn’t to add to the historical record so much as give his people a sense of their own traditions, customs, and, yes, history.

“In a recent visit to Wolford Canyon, where I was brought up,” he writes, “there was only silence. The memories remain, but the echoes of the canyon are calm. No children play in the springwater pools. No sweathouse fires heat the rocks. No deer hides are soaking. No buckskin tanning. No gardens. No wheat or hay growing. The fields are now teeming with juniper trees where the golden heads of wheat once swayed to the whispers of the wind.”

To replace that silence, Aguilar excavates the memories of people he knows and others whose reminiscences have been recorded. Out of these and his own experiences, he weaves a kind of handbook for Chinook descendants like himself, especially the younger generations of the 21st century, who have no contact with anyone who lived by the old ways.

In the midst of chapters that explore the Chinooks’ traditional foods (both plants and animals), religions and beliefs, myths and legends, and warfare, Aguilar includes set pieces on practices such as the sweathouse, meat drying, the use of traditional nets, and something known as “butt slapping,” a way for native fishermen on platforms over the Columbia River to indicate which fish they’ve caught they want to keep for themselves.

The chapter on salmon fishing on the Columbia is worth the book’s cost alone. Not only does Aguilar evoke the heyday of Celilo Falls, he also talks about salmon runs, salmon festivals, fishing techniques, and customs that regulated how and where the salmon were fished for.

In other sections, he writes about the other species the Chinook relied on–Pacific lamprey, crayfish, sturgeon, smelt–and gives an exhaustive list of the plants they ate or used in other ways, as well as how they prepared them.

Beginning with his own experiences in forced boarding schools and government programs, like one in the 1950s that attempted to get younger Indians to move off the reservation into cities, Aguilar takes us through the hardships his people have had to endure while also celebrating the endurance of a vibrant culture in danger of being completely lost.

One of the most important aspects of Aguilar’s project is his naming of individual tribal members, past and present–names that have been left out of the history books. He traces the lineage of individual names, tells us how names have been given, and looks at the meanings of those names. He is careful to name important local figures who are unknown to the general public and tell their stories too.

“The River People are the Northwest Klickitat and the Eastern-speaking Chinookan Kiksht,” Aguilar writes. “They are the Wascos, the Cascades, the Wishxams, the Clackamas, the Multnomahs, the Hood Rivers, the Skamanias, the Skilloots, and others who lived in villages on both sides of the Wilmaɬ, the Columbia River.”

By naming and writing for the descendants of these people–his people–Aquilar is trying to make sure they and their ways are not forgotten.

When the River Ran Wild!

Indian Traditions on the Mid-Columbia and the Warm Springs Reservation

by George W. Aguilar, Sr.

Published by Oregon Historical Press, in association with the University of Washington Press

2005

$24.95

Buy it here.

Leave a Reply