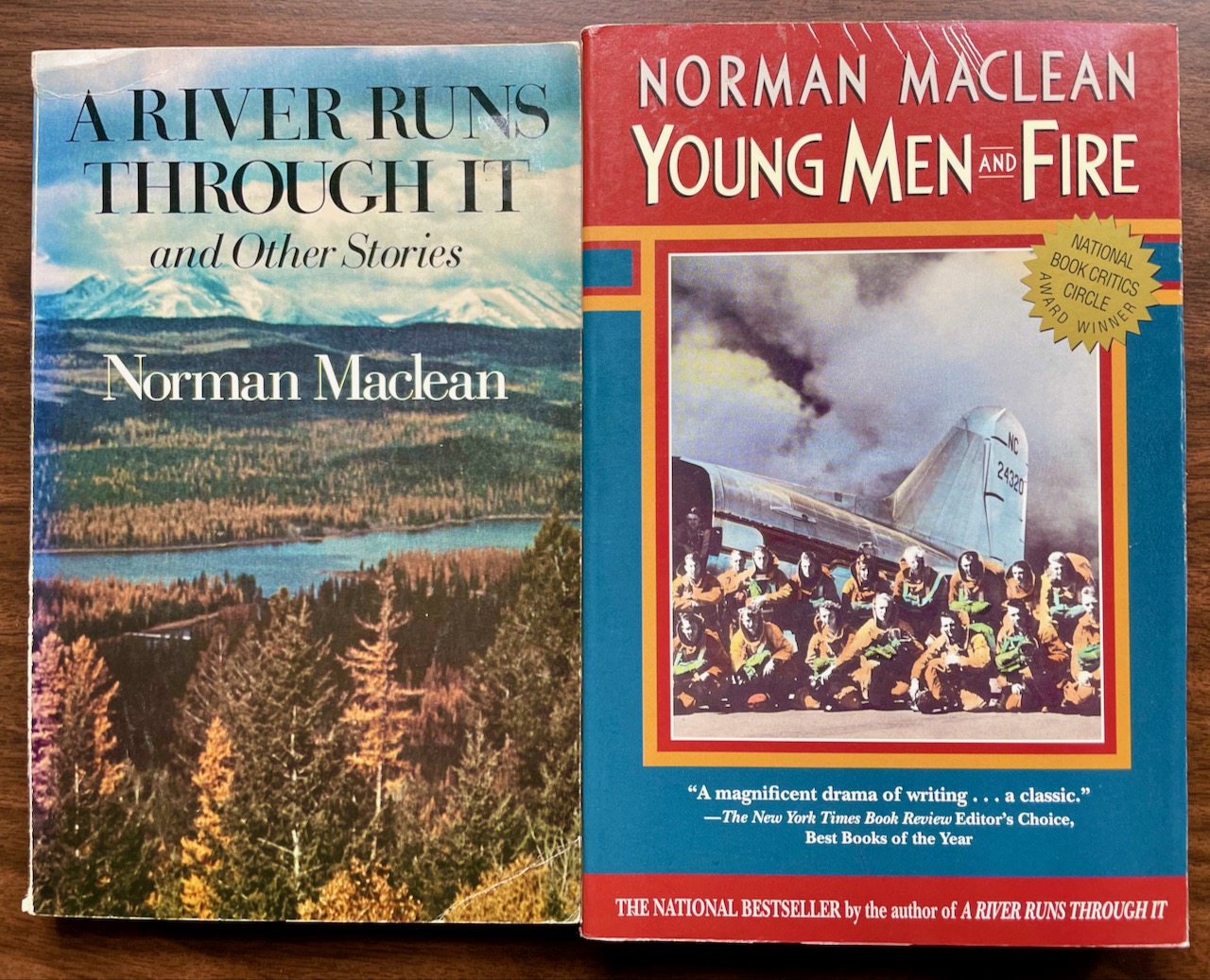

A lot of my writing on this site so far has been focused on Washington and Oregon as the core states in what we call the Pacific Northwest, but the writer most associated with Northwest writing is probably a Montanan–Norman Maclean–in part because Maclean’s two books, A River Runs Through It and Young Men and Fire are consciously about Northwest life: traditional Northwest life, iconic Northwest life, what we might call real Northwest life, for there’s nothing more Northwestern than his main subjects: fishing and trees.

But Maclean wrote about more than fishing and trees, of course–more even than family and fire. As James R. Frakes, who reviewed Young Men and Fire for the New York Times, wrote:

You can learn a lot from this book: detail-crammed pages on the special qualities of logging boots, on the delicate differences between ‘general and specials’ and ‘counter flies,’ on fighting forest fires, on the lost art of horse- and mule-packing, on cribbage, on draw poker, on iambic pentameter, and on ‘walking whorehouses.’ Also a lot about Montana, where drinking beer doesn’t count as drinking, where they don’t care whether the whiskey is much good if they can get strawberry pop for a chaser, and where being acquitted of killing a sheepherder isn’t the same as being innocent.

One of Maclean’s most important contributions to the literary world is his deft blending of fiction, memoir, and narrative nonfiction into something that is far more compelling and profound than if he had stayed in his lane, so to speak, trying to write only one of the three, as most writers are cautioned to do today. The one other writer I can think of who does something similar, though in a very different way, is W. G. Sebold.

Of course, Sebold wrote about places that have a long and valued literary tradition whereas Maclean wrote about a place the literary gatekeepers in New York and elsewhere gave little credence to. (Even the Frakes paragraph quoted above can be read as somewhat condescending.) As he relates in his Acknowledgements in River, Maclean had difficulty finding a publisher for his stories not only because he finished his collection when he was already in his 70s but also because they “turned out to be Western stories–as one publisher said in returning them, ‘These stories have trees in them.’”

In the end, it was the University of Chicago, where Maclean had been a professor for decades–teaching classes, creating programs, and helping students instead of doing his own creative writing–that published both of his books. Although the second one, Young Men and Fire, which he hadn’t quite finished when he died at 87 in 1990, dealt even more completely with trees (and those who fight the fires that threaten them), it won a National Book Critics Circle Award–a sign not that New York had embraced the Northwest but that readers had (and some of the wiser critics listened to them).

It was Robert Redford’s 1992 movie version of A River Runs Through It that transformed its central story from one readers loved into one embraced by the larger American culture. It was the Redford movie that made Maclean a household name. And it was his movie that turned western Montana into a mythical flyfishing paradise, leading to influx of wannabe fishermen and the buying up of former ranches and other rural lands.

But Maclean’s real Northwest, his traditional Northwest, his truly iconic Northwest is only approximated in Redford’s film. To find it, understand it, savor it, you have to dive into his books.

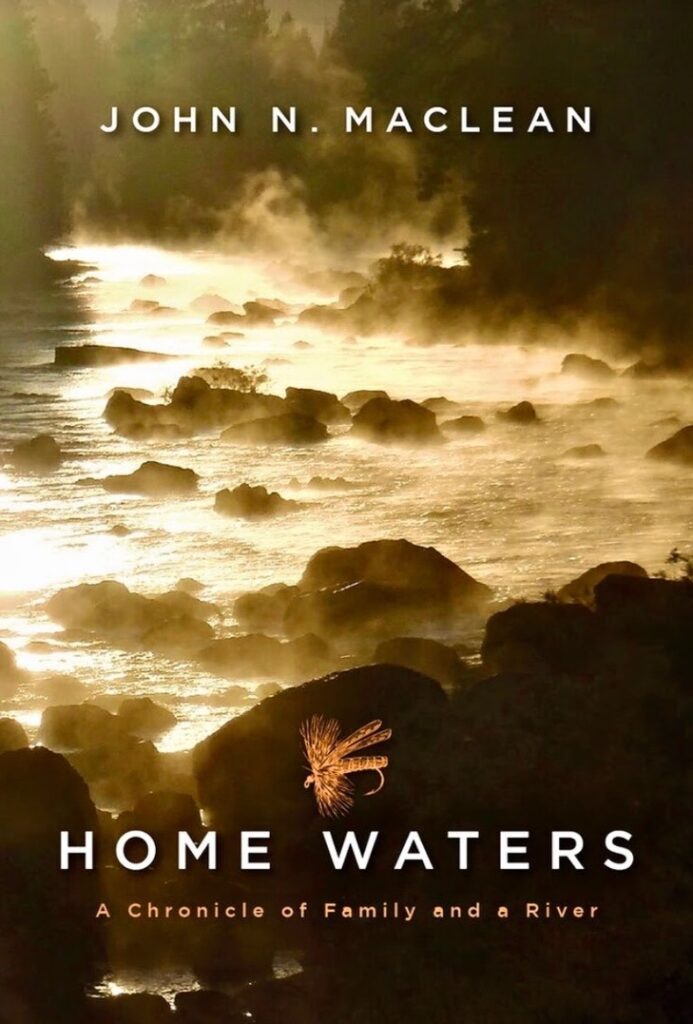

Note: For a deeper look at Maclean’s life and the real-life stories behind those in A River Runs Through It, check out his son John Maclean’s beautifully evocative and highly informative 2021 memoir, Home Waters: A Chronicle of Family and a River

Here are some links:

The University of Chicago Press’s Norman Maclean bio

Leave a Reply