by Bud Withers

[Bud Withers covered sports for decades in Eugene and Seattle. You’ll find his full bio at the end of this post, including information on his latest book, Mad Hoops. This writing is copyrighted and used by permission of the author.]

The other day, on the anniversary of the New York Jets’ ringing upset of the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III in Miami, ESPN showed a familiar video clip of Joe Namath lounging by the pool in the days before the game.

As an old journalist, I was inclined to assimilate that in old-journalist fashion: marveling at the access a TV cameraman had in 1969 to get a loose-and-easy shot of Namath.

When we think of today’s journalism compared to what I knew when I was coming up as a young reporter in 1970s Eugene, the difference is often about access, which is sort of the lifeblood of the business.

Of course, newspapers had more cachet then. They were a bigger deal. There was no online competition, so, if only by number of outlets, the local paper stood out.

I covered University of Oregon football in those days, and to further our insights into the Ducks, my sports editor and I finagled a weekly lunch session with the UO football staff. Every fall Wednesday at noon, we’d pick up sandwiches and an assistant coach would show us game film, talking candidly – and off-the-record – about players and big-picture strategy. Occasionally, the head coach did it.

Do you think Chris Petersen, the Washington coach a few years back, would have been party to something like this?

Closed practices? Practice was always open. Even Dick Harter, the Bobby Knight-like taskmaster who coached the Oregon basketball team, allowed media people into practice on the second level of old McArthur Court. In football, it was assumed you wouldn’t write about the double-reverse pass they were practicing, and the matter of practice injuries was something to be negotiated. But practices were open, unfailingly.

I covered the Hall of Fame curmudgeon Ralph Miller when he coached Oregon State basketball. Practice went from 2 to 4 p.m., and on multiple occasions, I was in his office interviewing him at 1:30. Two o’clock would come, 2:02, 2:03, before he’d pull himself away, knowing he hadn’t missed anything.

Not only in the ‘70s, but for decades later, access remained relatively easy. The University of Washington had football media lunches and afterwards, coaches like Jim Lambright and Rick Neuheisel would routinely hang around, entertaining the one-on-one questions you didn’t want to ask in the group session.

In the 1990s, I worked at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, which didn’t have a Sunday paper (anathema to a guy covering Saturday’s college-football game). So I convinced Lambright and the Washington publicist that we needed a Sunday-evening call from the coach to update the day-after view of the game for the Monday-morning paper, simply because we were disadvantaged. It wasn’t Lambright’s favorite thing, and he sometimes missed it, but he usually came through.

We struck deals with coaches. I don’t say that with pride, but we did it. I’d like to think it was mostly because of the paucity of news outlets–and a belief that a greater good was being served–than any shady relationship with the teams we were covering.

One time, an announcement came that a coach’s contract had been extended. I sought reaction, and to my surprise, several players issued a no-comment response. All of them were African American. It couldn’t be coincidence.

It would have been perfectly justifiable simply to report this reaction. But my boss decided that would raise more questions than it answered (I agreed). And it probably would have been a career killer for the coach. So we arranged a meeting with him that night and confronted him with the details. I don’t recall how we finessed writing the story, but it didn’t center on Black aversion to the contract extension. Our stance was that we knew something important that could be of use later – and yes, the coach now owed us one.

The propriety of our approach is debatable, but my point is that today, I don’t think the story unfolds that way. The landscape is too competitive.

Two things have dramatically cut into access, changing journalism forever. First, the camera phone. Everything can now be proven, and anything is subject to revelation, including a team’s secretive switch to a different defense.

Second, the number of news outlets. Fueled by online sites, that number has doubled, tripled and quadrupled the amount of coverage. In my little sports realm, where a coach might once have had a healthy relationship with a veteran beat writer, he’s surrounded today by people he may not know. People with camera phones. It’s the path of least resistance simply to shut it down, so closed practices are now the norm.

You can trace the trend by the evolution of post-game interviews. Once, the locker room was open–a steamy, smelly place that yielded an unvarnished look at the game. Over the years, the locker room gave way to a meeting room or hallway where you could move from player to player. Now, increasingly, players are brought to a podium or interview table and, knowing they’re speaking to everyone, provide sterile responses that reveal little. Naturally, this pleases team management, which sets things up this way to control the message.

We could debate endlessly how much diminished access has hurt journalism. Just know that when you see an exceptional newspaper story or an exemplary piece on TV today, it’s usually in spite of access, not because of it.

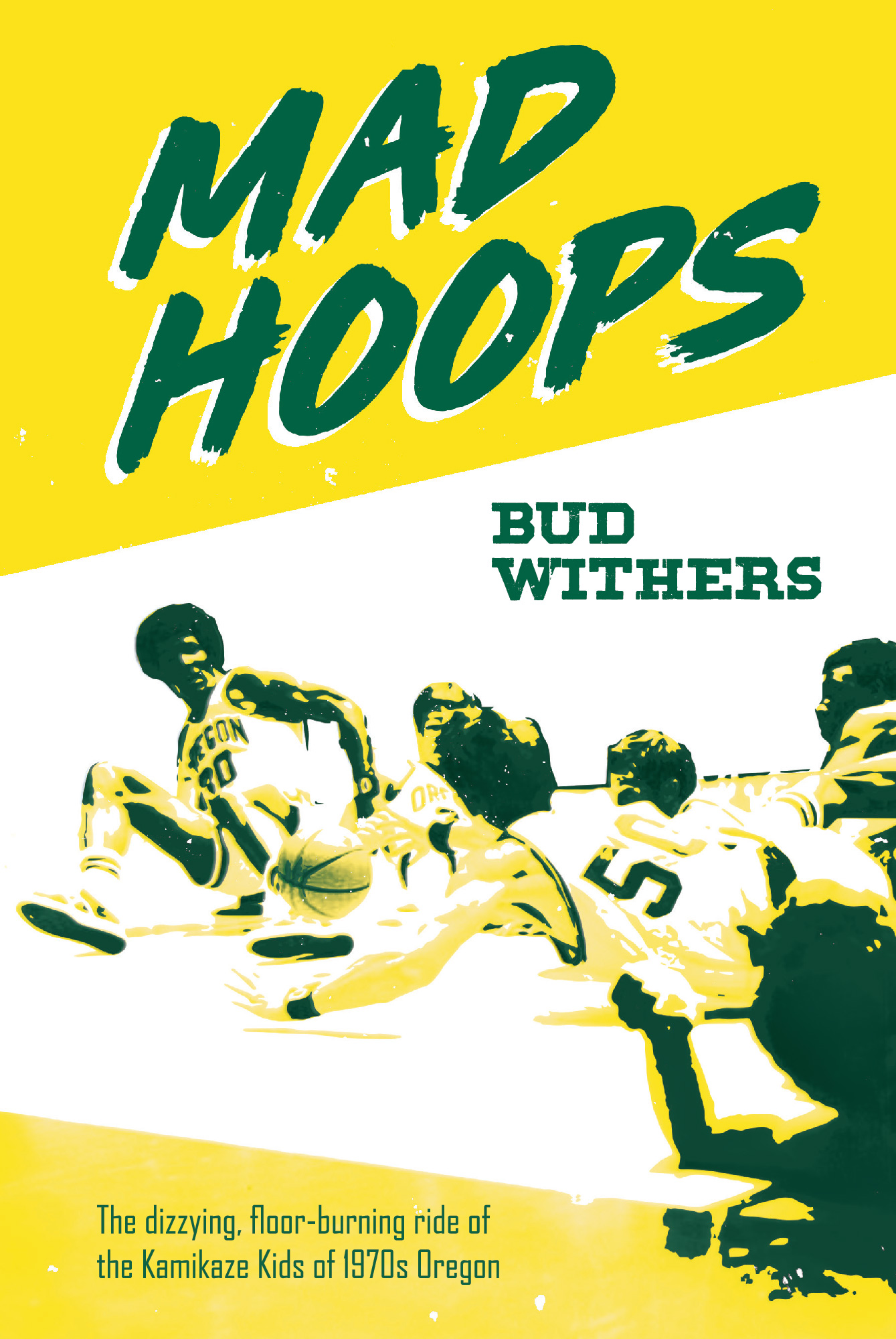

Bud Withers wrote for three Northwest dailies during a 45-year career in the newspaper business. A member of the U.S. Basketball Writers Association Hall of Fame, he has authored five books. The latest, Mad Hoops, on the frenzied seven-year run of University of Oregon basketball’s “Kamikaze Kids,” is available at Amazon and Bookshop.org.

Click here for a Portland Tribune review of Mad Hoops.

Leave a Reply