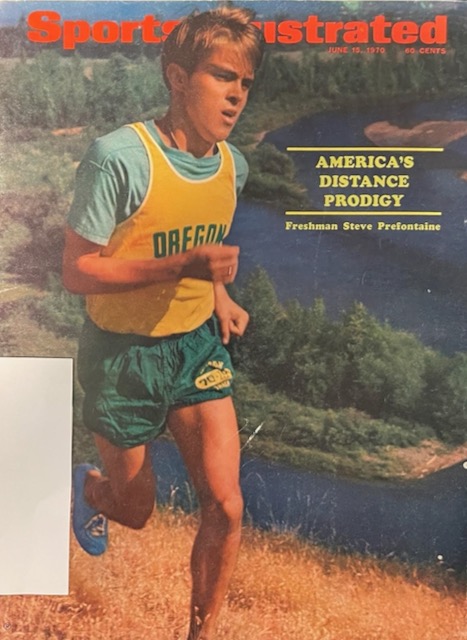

For some reason, when I was 12 years old, I bought a subscription to Sports Illustrated with money I’d made delivering the Seattle Times. Of the 50 or so issues mailed to me that year, I’ve held on to exactly one. Its cover has a full-bleed photograph of a freshman runner at the University of Oregon the magazine calls “America’s Distance Prodigy.” The runner looks a bit like me at that age – a similarity I didn’t see until someone pointed it out when I was a freshman at Oregon myself six years later.

As most track fans would guess, the runner was Steve Prefontaine, who, by the end of his short life, had set American records in every distance from 2,000 to 10,000 meters. That end came just a year before I enrolled at Oregon, and images of Pre (as he was known) were everywhere. Somehow I acquired my own huge poster and hung it in my dorm room, honoring someone I’d been too young to follow while he was alive.

Because Pre was only 19 years old in 1970 and had only recently begun running against international competition (losing badly), he didn’t hold any records yet. SI‘s article was more about his potential and his legendary coach, Bill Bowerman, than it was about his accomplishments. The subtitle above the article (written by legendary boxing writer Pat Putman) said only that Pre “may turn out to be the best ever.”

Although he never set a world record or won an Olympic medal, if we’re talking about those who had the greatest influence on distance running in America, Pre was almost certainly the best. Not only was he dominant on the track, but he played a pivotal role in helping U. S. athletes break free of the draconian hold the Amateur Athletic Union had on them before he came along. He helped open the door to future accomplishments by making it possible for Olympic-class American athletes to receive outside support and still retain amateur status.

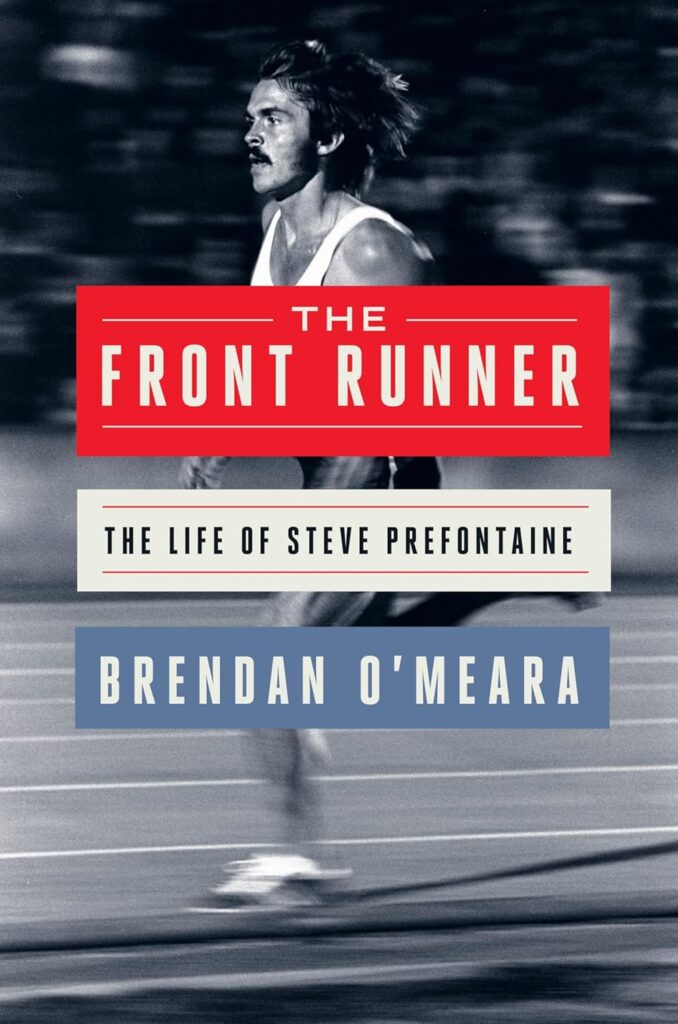

I discovered a few things about Pre just by being at Oregon, including the basic facts of his death at only 24—in a single-vehicle crash in the hills above the university. But it wasn’t until I sat down to read Brendan O’Meara’s The Front Runner: The Life of Steve Prefontaine (published by Mariner Books last May) that I learned all the ins and outs of his fascinating life and career.

O’Meara is the founder and host of the Creative Nonfiction podcast, which “showcases leaders in narrative journalism, essay, memoir, documentary film, radio and podcasts about the art and craft of true stories.” He’s also a sportswriter who lives now in Pre’s adopted hometown, Eugene, Oregon. The Front Runner is his first biography, and while some of his inexperience in the genre shows, his book brings Pre the runner and gadfly to thrilling life.

True to his sportswriting background, O’Meara is at his best when describing Pre’s races, including the lead-ups to them. He also does well at recreating Pre’s youth in his birth town of Coos Bay, Oregon, including the warm and careful way his high school coach, Walt McClure, guided him through the beginnings of what was already a promising career. I’ve never been to Coos Bay, but I could see its streets and beaches as O’Meara described Pre running along them.

I could see and feel the excitement in the UO’s old Hayward Field as well, when Pre’s People, composed of his most rabid fans, cheered him on to victory after victory. I knew the field from attending meets there in college (before it was torn down to build the sleek new facility in what is known, thanks to Pre, as TrackTown USA) but O’Meara made me feel what it was like at the height of Pre-mania.

I would have liked a bit more in the book about Pre’s later personal life (including his relationships with women who are introduced as girlfriends but never fleshed out), but O’Meara does a fine job of showing how Pre became a leader among his fellow athletes despite a brashness that often spilled over into arrogance.

One of the book’s many strengths is O’Meara’s careful presentation of Pre’s relationship with the then-fledgling shoe company Nike, founded by Bowerman and a runner he coached, Phil Knight. Pre was the first athlete to wear Nike shoes in competition. And although the AAU’s strict definition of “amateur” didn’t allow him to cash in as the kind of poster athlete Michael Jordan would be, O’Meara makes a strong argument that, without Pre, Nike would never have become the sports juggernaut it is today.

Two of the most important things in writing a biography are making your reader feel that the person you’re writing about was extraordinary in some significant way and bringing your subject fully to life. Judging by the deepened respect I have now for Pre and how profoundly I reacted to the book’s description of his death, I’d say O’Meara succeeded in both areas.

“Pre, you see, was troubled by knowing that a mediocre effort could win a race, and a magnificent effort can lose one. Winning a race wouldn’t necessarily demand that he give it everything he had from start to finish. He never ran any other way. I tried to get him to. God knows I tried. But Pre was stubborn. He insisted on holding himself to a higher standard than victory. A race is a work of art. That’s what he said. That’s what he believed. And he was out to make it one every step of the way.”

Bill Bowerman in his eulogy at Pre’s funeral (p. 268)

A post-script: One of the key figures in that 1970 SI article and O’Meara’s book is assistant track coach Bill Dellinger, who would take over from Bowerman as head coach in 1972 and lead the UO program to even greater heights. I didn’t know until I read The Front Runner that Dellinger won a bronze medal in the 5,000 at the 1964 Olympic Games or that he played a vital role in Pre’s development. But I did know Dellinger himself.

In my senior year at Oregon, I signed up for a class in the decathalon Dellinger taught. At the first or second session, he had all of us run a timed mile. I’d played basketball in high school and was a recreational runner, but I’d never run a timed mile. When I finished in five minutes flat, Dellinger came over to me and asked my name, along with several other questions. Was he looking for a new decathlete? I wondered. Did my time impress him, coming as it did in what was only a PE class? I never found out. A couple days later, I came down with appendicitis and had my appendix removed. The doctor told me to avoid strenuous activities for at least five weeks. I had to drop the class.

Although he was Pre’s coach, Dellinger outlived his former student by 50 years. He died on June 27, 2025, at the age of 91. According to Wikipedia, “In his 25 years of coaching, Dellinger’s men won five NCAA titles, achieved 108 All American honors and had a 134–29 meet record. He was the Pac-10 coach of the year multiple times.”

As O’Meara makes clear, Pre was blessed not only with what Dellinger, in that SI article, called “a cardiovascular system that is so superior to the average human that it is almost unbelievable,” but also with some of the finest coaches to ever lead a program in any sport.

Sign up on our home page to have future Writing the Northwest reviews and articles delivered directly to your inbox!

Links:

Leave a Reply