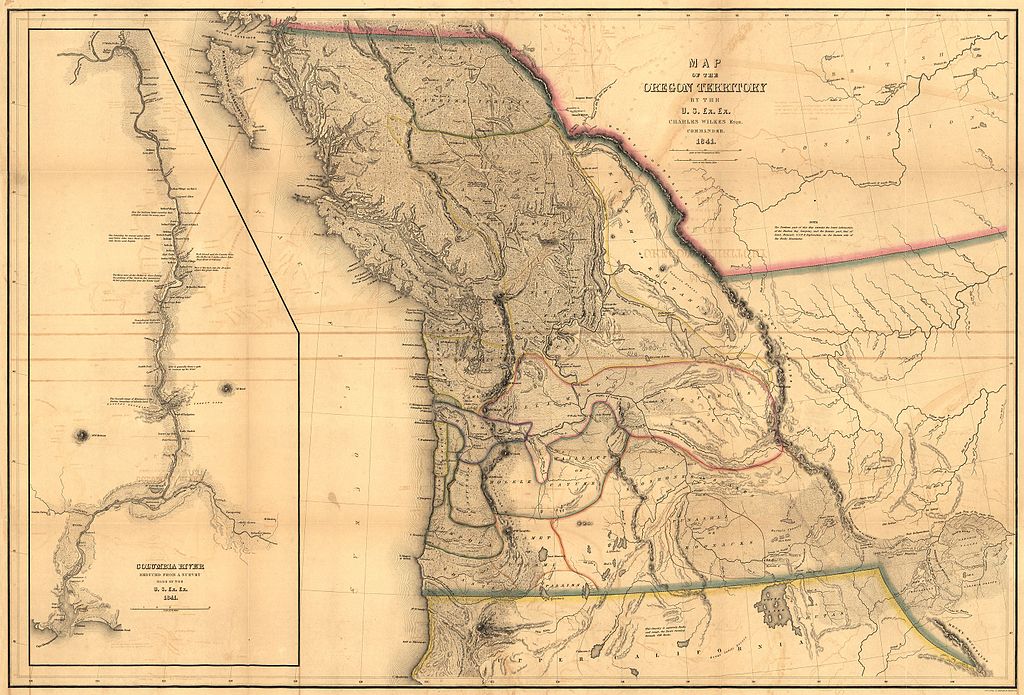

Before we talk too much about writing the Northwest, we should attempt to define where and what the Northwest is. One of the few writers who has tried to write comprehensively about the region, historian Carlos Arnaldo Schwantes, who taught for many years at the University of Idaho, has written:

The fact is that Pacific Northwesterners themselves cannot agree upon their region’s bounds. In addition to the generally accepted core states of Washington and Oregon, some people would include western Montana and even northern California and British Columbia within the region. Idaho presents the greatest challenge to easy classification because some residents perceive their state as oriented toward Oregon, Washington, and the Pacific Rim, while others consider it part of the intermountain West that includes Montana and Utah….Some scholars classify Oregon and Washington within the Far West or Pacific states and Idaho within the Mountain states, or the separate the lush, green Douglas fir country of Oregon and Washington west of the Cascade mountains from the high, often arid interior.

Schwantes ultimately settles on the complete states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho for the purposes of his book. “Several unifying forces operate within this 250,000-square-mile region,” he writes, “the Columbia River and its numerous tributaries, networks of transportation and communication, patterns of trade and commerce, and a special sense of place derived from history and geography. These integrative forces lessen internal divisions caused by mountain ranges, distance, state boundaries, and differing economic activities and political and religious cultures.”

These words are in the “Revised and Enlarged Edition” of Schwantes book The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History, published in 1996. In the 25 years since that edition appeared, those “integrative forces” seem to have become less integrative. Today, there’s a growing movement in some Oregon counties to secede from that state and become part of Idaho, which some residents feel is a better fit culturally, politically, and even geographically. In both Washington and Oregon, the wetter western half seems to be perennially at war over issue after issue with the dryer eastern half. Many residents in the Klamath Basin identify largely with the drainage area of the Klamath River, which crosses from Oregon into California. In some recent summers, wildfires in British Columbia laid blankets of smoke over Washington, suggesting at least an environmental link between those two entities. And in 1964, a 9.2 earthquake in Alaska (which some historians have argued should be considered part of the Pacific Northwest) set Seattle’s Space Needle swaying.

If we consider the older connections between indigenous populations, we find other patterns and alliances, such as the similar cultures along the Pacific coast above and below the current US-Canada border and the trading centers along the Columbia River that drew people from tribes near and far.

Then there’s the Cascadia Movement, dedicated to the forming of an independent nation composed of the current-day areas of Oregon, Washington and British Columbia—the core of the s-called “Cascadia bioregion.” According to Wikipedia, Cascadian secessionists “generally state that their political motivations deal mostly with political, economic, cultural, and ecological ties, as well as the beliefs that the eastern federal governments are out of touch, slow to respond, and hinder provincial and state attempts at further bioregional integration.”

We could divide ourselves up in many other ways too: loggers vs. farmers, salmon country vs. wheat land, predominately urban regions vs. those that are mainly rural, mountain land vs. flat land, places where dams are mostly for power vs. those where they’re seen as mostly for irrigation, diverse areas vs. those with more of a monoculture.

In the end, though, what makes the Pacific Northwest interesting and worth writing about is that it has all of these various geographical, environmental, historical, cultural, occupational, political, and natural elements. And historically, the divide between these micro-regions was less pronounced than it seems to be today. People think of transient populations as appearing mostly in big cities now, but migrant farmworkers have long moved through the Northwest’s farming regions, and throughout Northwest history ad hoc groups of workers, mostly men, have gravitated from logging to harvesting to work or idleness in towns and cities.

So what are the boundaries of the Pacific Northwest? For the purposes of this website, let’s say it is centered in the core states of Washington and Oregon but includes Idaho and at least half of Montana and maybe parts of lower British Columbia too. But if someone writes about two explorers sent across the country by a president to find a Northwest Passage, or a college kid from Seattle who earns money in a cannery in Alaska, or the division of water rights on a fragile river that flows from Oregon into California, or the migration of Mormons across the Idaho-Utah border, all of that is welcome here too.

I’m interested less in strict definitions than self-identifications and the kinds of re-definings that make anything, from a person to a region to a concept, fresh and new.

Leave a Reply