Why do certain books affect us deeply while drawing no more than a shrug from other readers?

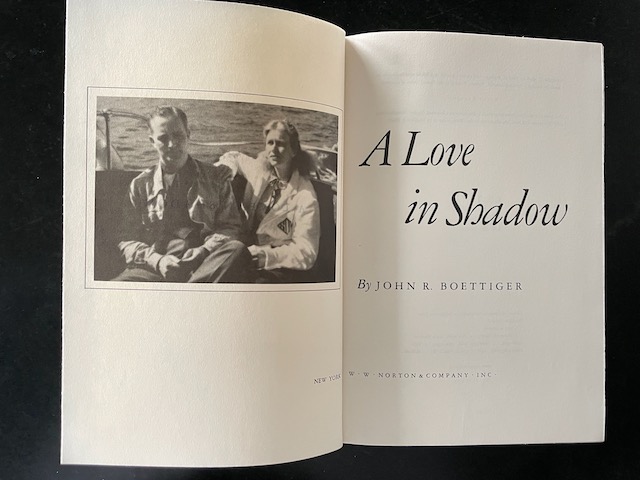

A while back, while researching President Franklin Roosevelt’s connections to the Pacific Northwest, I learned that his eldest child and only daughter, Anna, lived in Seattle for six years with her second husband, John Boettiger. At the time, Boettiger was the publisher of the Post-Intelligencer, a Hearst-owned newspaper. Intrigued, I looked for more information on their time in the city and discovered a book about their marriage, A Love in Shadow, written by their son, John Roosevelt Boettiger.

The book was published in 1978, three years after Anna’s death, and it doesn’t seem to have sold well. The only major review I could find online–from Kirkus Reviews–suggests it will appeal only to “addicts of Roosevelt family chronicles.” I’ve read my share of FDR books and other materials but I’m no addict. At least I didn’t think I was.

I tracked the book down at the University of Washington library and opened it to where the younger Boettiger begins writing about his parents’ marriage after chronicling how each of them grew up. It seemed at first it was the usual written-by-a-family-member fare. A puff piece. Hagiography. Some of the first lines I read came from gushing letters between his parents in which they talked about having a perfect love.

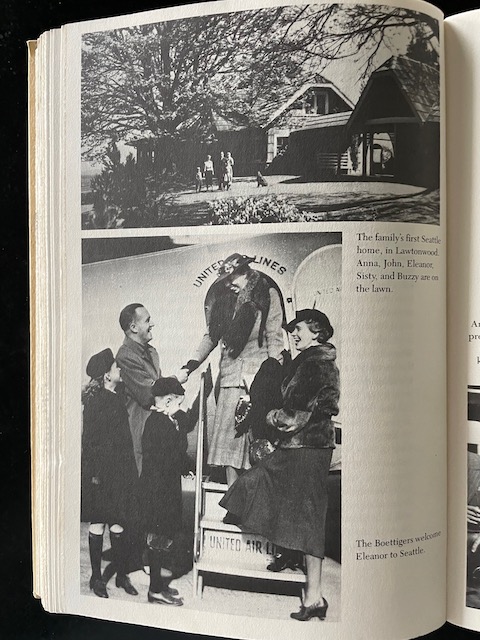

I read on only because I wanted information on their time in Seattle. I learned that Hearst hired Boettiger in 1936, when the P-I had gone through a brutal strike and was losing circulation and money. It couldn’t hurt to have the son-in-law of a popular president at the helm, right? Although Hearst leaned right and was known for his tight control of editorial direction, he gave Boettiger a free hand. Hearst had opposed FDR’s candidacy, but he could see what his readers wanted.

Hearst hired Anna too, but only to write about women’s issues for the paper’s “Homemaker” section. She worked as hard as her husband did to turn the paper around and soon they had increased both advertising and circulation. But in 1943, with America at war, Boettiger wanted to be where the action was. He talked his way into an overseas appointment as a captain assigned to “civic affairs.” He would never return to the P-I.

If my interest in the book had been limited to the Seattle connection, I would have stopped there. But I kept reading because, contrary to my first impression, the author didn’t paint a rosy picture of his parents or their marriage. In fact, before I’d read a dozen pages, he was diving deeper into all facets of their personalities, talking about his mother’s anxieties and the darkness that sometimes came over his father, spoiling and eventually ending their “perfect” union.

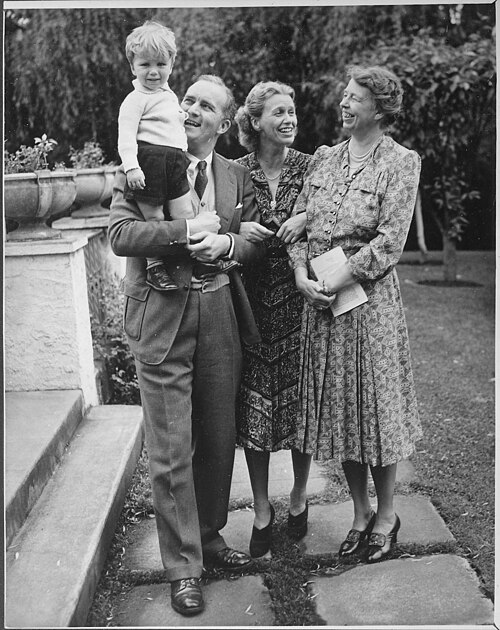

After reading from where John and Anna met during FDR’s first campaign through the book’s end, I turned to its opening pages and read the first half. There, I found an equally compelling study of Eleanor and Franklin’s growing up, followed by an intimate look at Anna’s childhood. The author’s sensitive and insightful writing made me feel more deeply than ever before what it’s like to be the child of famous parents, including the loneliness, the feelings of inadequacy, the pride, and the thrills.

When I finished the book, I googled John Roosevelt Boettiger and learned he became a clinical psychologist after working with his grandmother, Eleanor Roosevelt, when he was a young adult. It was his use of a psychological lens, combined with good research and a willingness to take an honest, clear-eyed look at his parents (and grandparents) that made his book such a captivating read for me.

One of the book’s strengths is the author’s use of letters and other personal documents. The most poignant piece is an unpublished essay in which Anna describes, in third person, a return to her family’s beloved estate, Hyde Park. She reflects on her childhood there, evoking the joy and love of family times and the peace and solitude of days alone. When a guard asks if she wants to go inside the house, she says no.

“The same trees were still there,” she writes, “the same lawns and fields sloping toward woods and river, the same walls, doors and windows.

“But it was all dead to her.

“There was no life behind those dark windows; the front door would not suddenly open and frame laughter and welcome.”

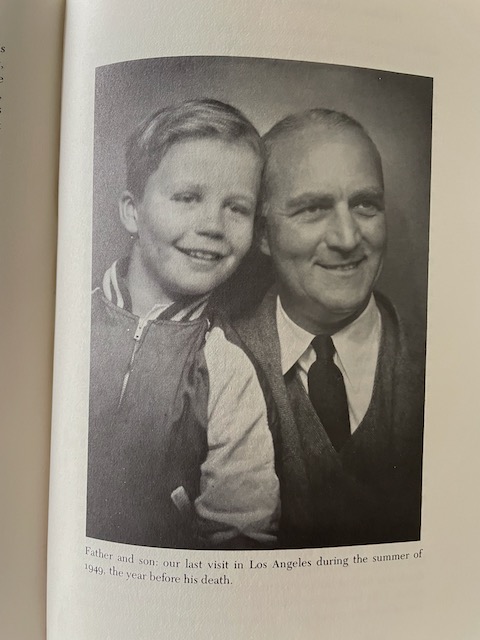

What Boettiger’s book does best is present all of life’s emotions writ large. Yes, the book is uneven and at times sentimental. Yes, it has an undercurrent of darkness. (Spoiler alert: After mostly happy days in Seattle, the Boettigers’ once-fairy-tale life disintegrated into failure, divorce, and, when the author was 11 years old, his father’s suicide.) But I came away feeling as if I’d lived not only the lives of the celebrated people inside it but also my own, for a second time. It caused me to look more closely at everything that has shaped me or might have shaped me. That’s the gift a good biography gives.

Oh, and I learned a thing or two about the Northwest too!

Links:

Leave a Reply