If you were looking for the least visible and most vulnerable people in North America, girls from Indigenous families in the upper reaches of British Columbia would be at the top of your list.

It’s a place where the one main road, Highway 16 (dubbed the Highway of Tears) “winds down from the plateau to the coast, through ever-narrower valleys where cedar and Sitka spruce and hemlock rise from beds of moss and ferns to form a near canopy. As the skies sink lower, the mountains loom higher. The air grows heavier as the highway draws closer to the Pacific, clinging to a ledge above the Skeena River…where the margin of error is only a few feet in either direction.”

Living mostly in small towns and on native reserves in families ravaged by poverty, oppression, broken marriages, and addiction, the odds are stacked against these girls from the moment they’re born. Even when the love of family and community members allows them to nourish dreams, they must navigate a remote land where violence and neglect far outweigh opportunities–and predators often lie in wait.

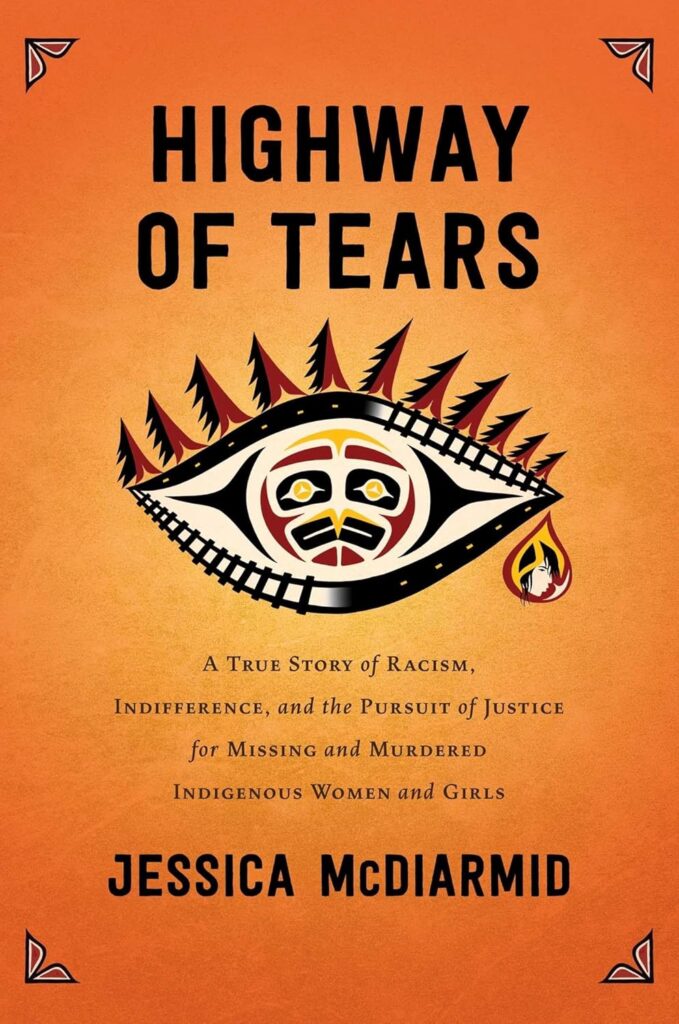

In Highway of Tears, journalist Jessica McDiarmid’s heart-piercing and acutely human exploration of the disappearances and murders of too many of these girls (and women) over the past fifty years, we learn their stories and see their world. We also meet the people they left behind, who struggle to overcome their own frailties and demons to keep the search for them–and the memory of them–alive.

Although McDiarmid often has little material from which to create a full picture of girls who go missing at 14, 15, or 16 years old, she manages to bring them to life through the words and actions of those who have lost them: their memories, their sorrows, their hopes. Despite the repeated failures of governments, Mounted Police, and media to take their losses seriously or offer more than mere words to improve the conditions in which they live, these loved ones work to build safer and stabler communities.

While maintaining a compassionate eye, McDiarmid doesn’t spare us the grim statistics and details:

- Indigenous women are six times more likely to be murdered than non-Indigenous women in Canada;

- Indigenous children are far more likely to be taken from their families by government agencies;

- Almost 50% of children taken before their first birthday end up in the criminal justice system;

- There is no transportation system and only spotty cell service along Highway 16, which cuts across the northern BC region from Prince George to Prince Rupert, linking primarily Indigenous communities.

But in a book focused on one of the worst things any family can imagine—the disappearance or murder of a child—McDiarmid manages to create a deeply sympathetic and even life-affirming picture.

What is most important about her book, perhaps, is that she names and puts faces and families to the victims she spotlights: Ramona Wilson, Delphine Nikal, Roxanne Thiara, Alishia Germaine, Lana Derrick, Alberta Williams, Nicole Hoar, Tamara Chipman, Aielah Saric-Auger, and others.

McDiarmid interviews detectives and others who worked on these cases and gives voice to their frustrations, sympathies, and pain as well. She also details the failures and indifference of politicians, civic leaders, journalists, and systems. But while she makes sure to convey the awful effects of racism, colonialism, prejudice, and addiction, she centers her story on the precious lives that are lost.

About Ramona Wilson’s early years, she writes:

The house changed when the baby came in the door. It got louder, happier. Each year on her birthday, they threw a big party. As she grew, her brothers doted on her, carrying her wherever she wanted to go, treating her like a little princess…it was her brothers Ramona cajoled into coming to her tea parties and letting her style their hair. She was a jokester. ‘Watch your head!’ she’d shout before her foot whizzed by one of her brother’s ears as she tested out her flexibility. Wherever she went, she sang in a lovely lilting voice and a peal of delighted laughter followed her.

Ultimately, McDiarmid lets us, her readers, decide where the faults lie and how complicit we are ourselves in letting oppression, neglect, prejudice, and tolerance of male violence continue to foster the conditions and acts that took these young women’s lives. It’s impossible to read this compassionate book without feeling a deeper responsibility to the most vulnerable in all our lands.

Two excellent Northwest literary novels related to the issues in McDiarmid’s book are The Child Finder, Rene Denfeld‘s sharp, suspenseful story of a woman whose job is looking for lost children and the child she’s currently searching for, and Perma Red, Debra Magpie Earling‘s deeply evocative and searing story of a young woman trying to survive on a Montana reservation.

Links:

Other writings by Jessica McDiarmid

The Gitxsan people of NW British Columbia–The Canadian Encyclopedia article

The Tsimshian people of NW British Columbia–American Museum of Natural History

“Peoples of the Skeena”–1949 film from the National Film Board of Canada (15 min., free)

The Child Finder by Rene Denfeld on Bookshop.org

Perma Red by Debra Magpie Earling on Bookshop.org

Note: I’m an affiliate of Bookshop.org, where your purchases support local bookstores. If you buy a book through a click on this website, I’ll earn a small commission that helps defray the costs of maintaining WritingtheNorthwest.com.

Leave a Reply