by David Naimon, co-author of Ursula K. Le Guin: Conversations on Writing

[Editor’s note: The following is Naimon’s foreword to a new collection of writings by Portland writers called Dispatches from Anarres: Tales in Tribute to Ursula K. Le Guin, edited by Susan DeFreitas and published by Portland-based Forest Avenue Press. In it, he discusses how Le Guin’s science fiction and other imaginative works reflect her experiences of living in the Pacific Northwest. You’ll find more information about Naimon and the book at the end of the post. This writing is copyrighted and used by permission of the author.]

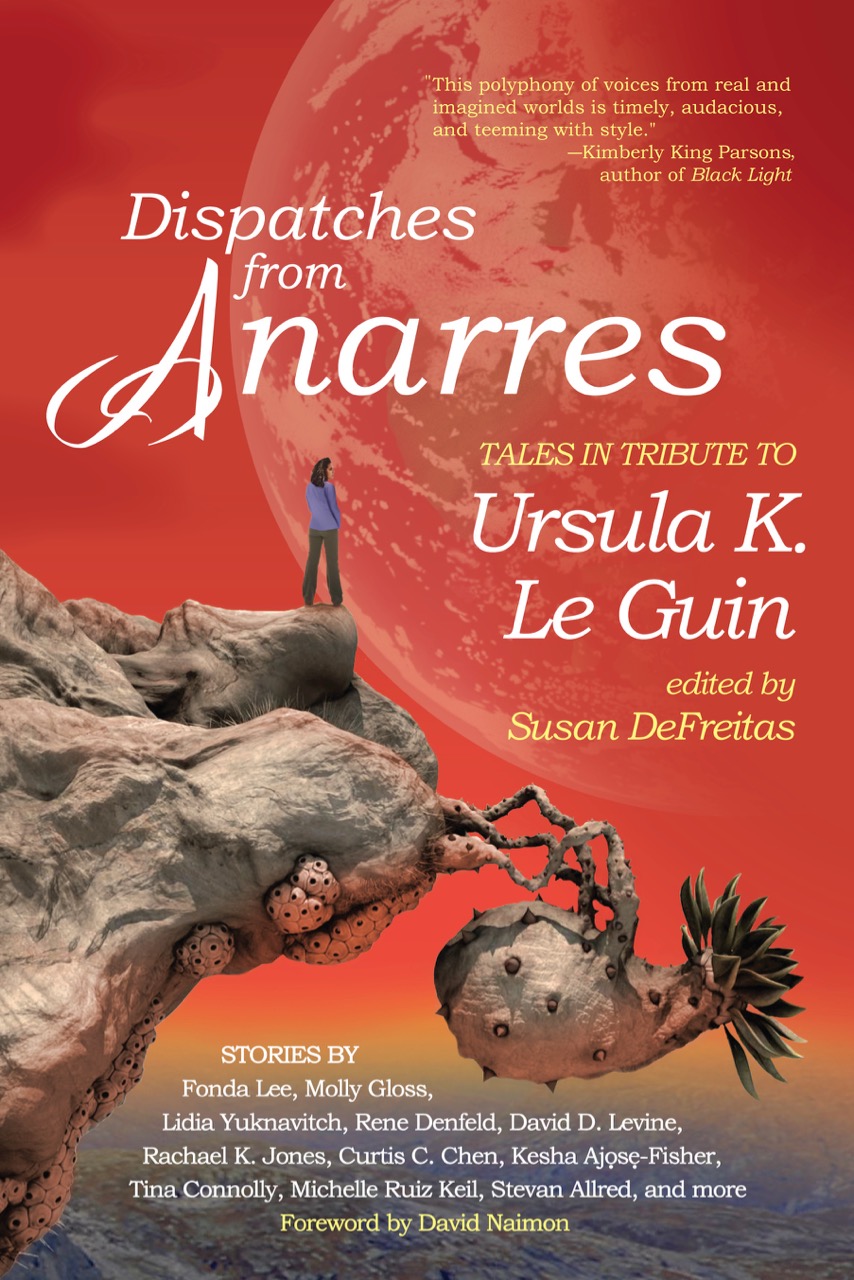

Dispatches from Anarres is a tribute to the vision of Ursula K. Le Guin from writers who either live in or have a strong connection to Portland, Oregon, the city Le Guin called home for sixty of her eighty-eight years. The premise behind this book is not only that Portland shaped Le Guin’s writing but also that writers who live in Portland, who walk the same streets Le Guin once walked, in turn have been shaped by Le Guin, arguably Oregon’s greatest writer.

But are either of these notions, when examined, actually true? Yes, one of Le Guin’s canonical science fiction novels, The Lathe of Heaven, is set in a future Portland, but for the most part her science fiction and fantasy novels are set in imagined other worlds. Should we therefore consider Le Guin’s relationship to Portland in the same way we do Alice Munro’s to southwestern Ontario or Gwendolyn Brooks’s to Bronzeville, Chicago—places these writers’ work seemed to emerge from, be fed by, and grow out of? Le Guin often wrote about the importance of the imagination and put forth a philosophy that, interestingly, did not place the imagination in opposition to the real. Can a book be truly called “realistic” if it does not include the imaginative, given that our imaginative faculties are so central to what makes us human? Or as Ursula put it(more pithily than I ever could): “People who deny the existence of dragons are often eaten by dragons. From within.” And: “Children know perfectly well that unicorns aren’t real. But they also know that books about unicorns, if they are good books, are true books.” Le Guin was quick to point out that many of our foundational cultural texts, from Beowulf to Don Quixote, from The Odyssey to Hamlet, are in fact fantastical, imaginative works that are also true and real ones.

Outside of science fiction and fantasy, Le Guin did directly engage with “the real world.” Her poetry and nonfiction often explicitly spoke to the geography, culture, and ecology of Oregon and northern California. From a meditation on the street where she lived to poems written from her favorite cabin in the remote Steens Mountain region (where her family briefly homesteaded generations ago), these writings are rooted in the “here” of place. But when it came to her fiction, she said: “I seldom exploit experience directly. I do what the poet Gary Snyder calls ‘composting’—you let everything you do or think or read or feel sink down inside yourself and stay in the dark, and then (years later, maybe) something entirely new grows up out of that rich darkness. This takes patience.”

If everything Le Guin did or thought is part of this composting process—the process that led to the world of Earthsea and the planets of the Hainish cycle—then the metaphor of composting seems not a metaphor at all. Le Guin and the landscape she inhabited, literary and geographic, were inseparable. A founder of Oregon Institute of Literary Arts (the precursor to Portland’s most prominent literary organization, Literary Arts), she also taught writing workshops at Portland State University, at the Malheur Field Station in remote Harney County, Oregon, and at Fishtrap in the Wallowa Mountains. She was an enduring supporter of Portland’s KBOO community radio and of West Coast small presses, from the feminist sci-fi press Aqueduct in Seattle to Tin House in Portland to the anarchist AK Press in Chico, California. She explicitly credits the landscape of the Steens Mountain region of Oregon as an inspiration for The Tombs of Atuan, and that of northern California for Always Coming Home—and one could imagine, standing atop the high point of Orcas Island, Mount Constitution, in northern Washington, overlooking the watery wonderland of that island archipelago, that it too could’ve been a wellspring, if not the wellspring, for the world of Earthsea. Le Guin’s imagination arose from the Cascadia bioregion, and she continued to weave herself from it and back into it again. Her imaginative composting came from and returned to this land, this earth in particular. Taken in this light, Susan DeFreitas’s twinning of Portland and Anarres—not as a reductive one-to-one correspondence, but as a mysterious union of the real and the imaginative—makes sense.

In Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, Anarres, the smaller planet in the double planetary system it shares with Urras, is considered lesser, not a planet at all, but rather a moon, a “rebel moon,” by its larger, wealthier, capitalistic, patriarchal neighbor. Long ago, in order to stop an anarchist rebellion, Urras agreed to allow the revolutionaries to live as they saw fit on Anarres, signing a noninterference pact to that effect. The anarchist society that arose on Anarres considered itself free and independent of the old world largely thanks to this pact.

For the longest time, Portland too was left alone, the forgotten big city on the West Coast. Without the immediately dramatic and stunning settings of San Francisco, Seattle, and Vancouver, Portland was a quiet inland port, one that lacked the scope of international commerce and cosmopolitan cultural influence of its outward-facing neighbor cities. And it was here, out of the spotlight, far from the hype, that artists and writers and dreamers, attracted by the cheap rent and affordable cost of living, were drawn to reinvent themselves. Whether it was the DIY ethos that developed here, the farm-to-table relationships that supported the local food movement, the family-like network of writers that emerged, or the radical acts of civil disobedience to protect the environment or protest the latest war (so prevalent that the first President Bush called Portland “Little Beirut”), the city emerged in many ways as a rebel moon.

Le Guin believed the notion of home was both imaginary and very real. “Home isn’t where they have to let you in. It’s not a place at all. Home is imaginary. Home, imagined, comes to be,” she said. “It is real, realer than any other place, but you can’t get to it unless your people show you how to imagine it—whoever your people are.” It is easy to imagine that these people—the tree sitters, the DIY artists, the community organizers—were not only inspired by Le Guin’s writing but also showed her how to imagine it. Le Guin was a listener, and a composter of what she heard. She advocated fellow feeling for the nonhuman “other,” for plants, animals, rocks, rivers, and even the tools we have fashioned from what the world has given us.

No wonder the stories of her fellow Portlanders, these dispatches from Anarres, include tales of women coming of age, women coming into their power, of tree-like networks in our brains, of tree-like networks as our brains, of the inquisitive and nostalgic remembrance of humans by ant collectives, and discussions of rebellion among bees. But there are tales that reveal the darker side of Portland as well. There is a reason Le Guin subtitled The Dispossessed “an ambiguous utopia.” Le Guin didn’t see the world through rose-colored glasses. Nor did she see Anarres or Portland this way.

As Jo Walton has pointed out, “Anarres could so easily be irritatingly perfect, but it isn’t. There are droughts and famines, petty bureaucrats and growing centralization of power.” And Portland’s self-regard, its self-mythologizing, its imagining itself into being as a place of self-reinvention, has often been fueled by historical and cultural amnesia. Founded on stolen indigenous land, built on the idea of racial exclusion, many Portlanders live here without a sense of the city’s history of redlining and displacement, of lash laws and internment. And as Portland has entered the spotlight, succumbing to a hype it had avoided for so long, housing prices have skyrocketed, the homeless population has exploded, communities of color have been pushed to its periphery, and Portland’s own utopic mythology has rightfully been called into question.

Samuel Delany suggests that the term “ambiguous utopia” is not meant to apply to Anarres in particular. That the peoples of Urras and Anarres both mistakenly believe they are living in a utopia. That Le Guin is questioning the notion of utopic visions altogether. “It’s only by problematizing the utopian notion,” Delany said, “by rendering its hard, hard perimeters somehow permeable, even undecidable, that you make it yield anything interesting.” This is what Le Guin has done. And under her spell, there are stories here that root the imaginative deeply in place, that suggest that there is no walking away from difficulty to create a happiness “over there.” Here we are, as in so many of Le Guin’s novels, in a place where people are imagining worlds into being that suggest both dystopic and utopic possible futures. Here we are with choices to make. About where to be, how to be, and what to imagine. Welcome to Dispatches from Anarres.

David Naimon is a writer and host of the literary podcast Between the Covers in Portland, Oregon. He is also co-author, with Ursula K. Le Guin, of Ursula K. Le Guin: Conversations on Writing (Tin House Books), winner of the 2019 Locus Award in nonfiction and a Hugo Award finalist. His writing can be found in Orion, AGNI, Boulevard, Black Warrior Review and elsewhere. It has received a Pushcart prize and been cited in Best American Essays, Best American Travel Writing and Best American Mystery & Suspense Stories.

~~~~~

Dispatches from Anarres: Tales in Tribute to Ursula K. Le Guin, edited by Susan DeFreitas

Forest Avenue Press, Portland, Oregon

Published: November 2021

366 pages

$18

Contributors: TJ Acena, Kesha Ajọsẹ-Fisher, Stevan Allred, Jason Arias, Stewart C. Baker, Jonah Barrett, Curtis Chen, Tina Connolly, Mo Daviau, Rene Denfeld, Molly Gloss, Rachael K. Jones, Michelle Ruiz Keil, Juhea Kim, Jessie Kwak, Jason LaPier, Fonda Lee, David D. Levine, Gigi Little, Sonia Orin Lyris, Tracy Manaster, James Mapes, C.A. McDonald, David Naimon (foreword), Tim O’Leary, Ben Parzybok, Nicole Rosevear, Arwen Spicer, Lidia Yuknavitch, and Leni Zumas.

Leave a Reply